A forum in celebration of Robin Darling Young and Joseph Wilson Trigg’s The Contra Celsum of Origen: English Translation and Facing Greek text (Washington and Cambridge: Harvard University Press/Dumbarton Oaks, 2026).

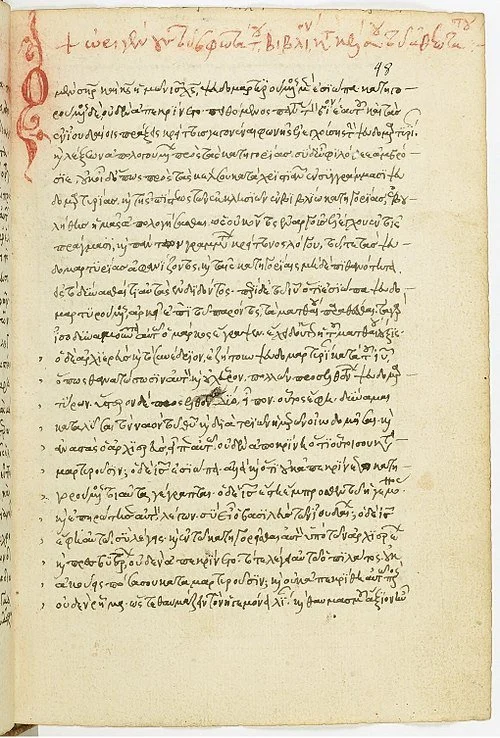

Joseph Trigg and Robin Darling Young posit the unabashedly philosophical character of Celsus’s challenge and Origen’s response as the basis of their project.

In this short tribute to Origen and his translators, I suggest that, among much else, Origen shows paradoxically how strong a mainstream polytheist’s case could be against Christianity in the second century, and how even a brilliant apologist could struggle to meet it.

A forum in celebration of Robin Darling Young and Joseph Wilson Trigg’s The Contra Celsum of Origen: English Translation and Facing Greek text (Washington and Cambridge: Harvard University Press/Dumbarton Oaks, 2026).

Celsus’ views about empire and cult, whether they were pagan or Christian, were far from dead in the fourth century; they appear in Christian sermons and treatises – not just in their pagan echoes in Porphyry and Julian.

Byzantium preserved Contra Celsum because it demonstrated that Christianity was compatible with Hellenism. Renaissance humanism welcomed it because, in doing so, Origen demonstrated that Hellenism was compatible with Christianity.

This book draws attention to one important but neglected concept from Hellenistic literary criticism that readers—including Christians—used to organize, describe, and evaluate narrative traditions.

The white spaces on the page can be spaces both of death and breath. Both are texts of drowning, the Egyptian enemies, their horses and chariots, and the African slaves, who were thrown overboard the slave ship in an insurance scam. Somehow, I believe, through this unconscious visual echo, these enemies and victims meet in God’s lament to the angels, (though perhaps this lament is addressed to all of us who sing victory songs): “my creations are drowning in the sea, and you are singing song?”

In the book’s conclusion, Raz offers weak prophecy as an alternative, reparative model, offering us doubt and circumspection instead of confident certainty, whether theological or nationalist. I would also suggest a second, complementary payoff. To me, the positing of an ancient source that is dogmatic, masculine, and assertively authoritative is one of modernity’s favorite alibis for its own violence.

A Memory of Violence offers a useful overview for anyone interested in understanding Chalcedon and its effects at a more detailed level, as well as those interested in the history of Christianity writ large.

Scully’s book commendably demonstrates the need for renewed and careful attention to a pattern of thought that has been treated poorly, and it does so with sharp analytical clarity.

“Ophir insists that he is not simply claiming the modern sovereign as a “secularized political concept,” but something deeper: a deification of the state itself, as the one concept that we cannot think without, just as the biblical writers could not imagine not being ruled by God.”