This piece is part of an ongoing forum devoted to the publication of A New Translation of Contra Celsum. See more here.

Had he been an Oxbridge man in the late nineteenth century, Celsus would surely have won a first. He could have gone on, like A.C. Tait, to be Archbishop of Canterbury – or like others from those universities, to be Viceroy of India, or the last Governor of Hong Kong. And not without merit would Celsus, were he to have been born a few centuries later, have reached the archepiscopal throne – by the end of the fourth century, and certainly the fifth, the Christian church from Persia to Spain needed his type: learned, philosophically literate, fitted to the manor by birth and elite training. Consider how as a boy he had mastered the enkyklios paideia of his day and displayed that learning in later life. He was trained in the Second Sophistic and was skilled in grammar and philosophy – one can only imagine what he would have done if he were a Christian at the opportune time. Perhaps he would have protected the newly-installed mos maiorum while he traced heresiology with his research team and administered a city with his deacons. And probably, as a “cosmic Tory,” he would have been happy to let the ruling class rule. If, as an adherent of traditional Roman religious views, the gods were on Olympus and the daimones in their glens and fountains, and the plebs were in their place, not much would change after baptism: the plebs would stay in their lane, and the ignorant and upstart Christians would know their place, while bishops represented the angels, saints, and Trinity.

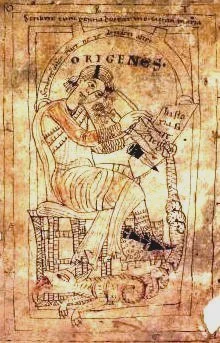

Celsus’ views about empire and cult, whether they were pagan or Christian, were far from dead in the fourth century; they appear in Christian sermons and treatises – not just in their pagan echoes in Porphyry and Julian. For like Celsus, these later authors had an interest in preserving the order expressed in worship and undergirded by philosophy, which they could now put in the service of a Christian empire. Had he been a Christian bishop, Celsus still would have been no friend of Origen -- because for all his training and genius, Origen knew a cosmic Tory when he saw one; but Origen made philosophy a ladder, not a wall. This is as true for Origen’s massive Contra Celsum as it is in his Protreptikos – the Exhortation -- to Witness.

In the late 240s CE, the Roman Empire was in the midst of a century-long crisis of governance. The Emperor Diocletian would eventually resolve that crisis by radically restructuring the Empire and moving its capital to the East. But already fifty years before his reign, Christians seemed threatening to that empire. The year 248 would be the year 1000 ab urbe condita. Some members of the Greco-Roman elite feared for good reason that their world might not outlast the Millennium of Rome. They also thought that they knew why: the gods were no longer worshiped as they once had been. Both the state and local patrons supported the civic cults, and the emperor-worship that held the empire together, and provided its rationale. But Christians of various sorts, a small minority in most places, were now increasing in number and persuading an ever-greater number of people to reject the worship of the gods. Pressure was growing to end this menacing problem. In 251 under Decius, such pressure would lead to an attempt to compel all citizens of the Empire to return to proper worship on pain of death, a persecution in which Origen would be arrested and tortured. Several years before that, though, in court circles, those who favored the suppression of Christianity were circulating an obscure work written eighty or so years earlier, the True Logos. Its author, Celsus, evidently a philosopher, had investigated Christianity and tried to show that it was incompatible with Greek and Roman culture, and subversive of the Roman Empire. Origen's wealthy and generous patron, Ambrosius, who had connections to court circles, asked Origen to provide a detailed refutation of Celsus's charges. He had previously commissioned other works, such as On Prayer and Exhortation to Martyrdom. The Contra Celsum, in eight books, the only extended work by Origen to survive nearly intact in Greek, fulfilled this assignment. While he had previously never heard of the True Logos, Origen was compelled by Ambrosius’s request to take it seriously.

Responding to a philosopher cum private investigator and prosecutor, Origen assumed the role of a rhetor – a defense attorney arguing aggressively, and repeatedly, exhaustingly, for the innocence of his community, its aims and its virtues. Yet he also wrote as what he was, a philosopher -- he had been trained as a philosopher in Alexandria, and still taught in that role in Caesarea -- to argue that Christianity was not the cause of the crisis in Roman governance, but because it itself was a trans-national politeia, it was a support to the peace and order of the politeia. He deployed his knowledge of ancient Greek literature, too, to support his case. In doing so, he produced a masterpiece of political philosophy, fusing the Platonic tradition with a Christian teaching grown as well from Jewish roots. Against both contemporary Christian dualists and Jewish opponents, Origen understood this teaching as a development and fulfillment of Jewish teaching and interpretation.

Origen was accustomed to debate and discussion with groups of “Hellenes” – adherents to Graeco-Roman practice and philosophy – and with Jewish teachers in Caesarea and perhaps elsewhere, and with Christians of various opinions and practices, including the simple Christians Celsus despised. The students at his didaskaleion were both Hellenic and Christian in practice and may have included Jewish students as well. And Caesarea, the major port city of Roman Palestine, brought trans-Mediterranean cultural traffic to the region – not unlike the larger entrepôt of Alexandria, where Origen had earlier taught both philosophy and scriptural interpretation.

Despite the threats against Christians and the growing importance of bishops as teachers in the expanding church, Origen maintained the role that Clement had outlined in the Alexandrian community: a philosopher teaching advanced students – Clement called them gnostikoi – who could pass beyond the elementary level of instruction and embark upon philosophy as a way of life. As both practice and contemplation, Christian philosophy self-consciously remained heir, even first-born heir, to the diadochē of Plato, and offered to its students the training according to Origen to ascend beyond the observable exterior world, returning to the original condition of the human as a rational being: a mind beholding all reality, as a christ again, divine.

But Origen’s views had opponents. The first was Demetrius of Alexandria, his first bishop; and their conflict led to Origen’s departure from that city. Opposition continued for different reasons in the work of Methodius of Olympus, another Platonist but, significantly, a bishop, who opposed Origen’s teaching. Methodius wrote dialogues in the Platonic tradition, but in his view, Origen went too far: he erred in his interpretation of the resurrection and the preexistence of the soul. Finally, at the end of the fourth century, another Alexandrian patriarch, Theophilus, joined in the opposition – as did the powerful monastic leader Shenoute of Atripe in his forceful sermon of the early fifth century called “I am amazed.”

Methodius’ objections, and those of other unnamed critics, elicited a response by Pamphilus and his devotee Eusebius, the beginning of an appreciation of Contra Celsum that would last until the last decades of the fourth century, when Epiphanius and Jerome began – in part thanks to their hostility toward Origen’s intellectual heirs and students in Palestine, and in Alexandria and the monastic settlements in northern Egypt – to turn against him. Methodius had been a prominent detractor shortly after Origen’s lifetime, but Origen’s own student Gregory, later "Thaumaturgus," wonder-worker as bishop of Neocaesarea, may have been the first to appreciate the potential usefulness of Origen’s portrait of a philosopher-Christian to the church as it settled into its urban and mediating role. His Thanksgiving Address to Origen preserved an indelible portrait of his teacher as a philosopher, and his heirs, the Cappadocians, and their younger associate Evagrius expanded upon both Origen's teaching and his role as an ascetic philosopher.

In his history of the church, Eusebius sought to incorporate Origen’s work into his own project, presenting the leaders of the Christian church, beginning with Jesus, as learned men who cared for the good of the Roman Empire and those rulers who favored the church. Eusebius promoted this view most obviously by pairing Origen with the martyred Bishop Dionysius of Alexandria in Book 6 of his Church History. Origen in his own writings seems to have accepted the necessity of bishops as presiders, but his own interest was not in ruling the church, but in the training of philosophers – and in the Psalms Homilies he once hinted that his own bishop inadvertently had invited a maleficent spirit into the congregation. Because Origen had composed the Protreptikos (better known as the Exhortation to Martyrdom) and because Eusebius presented Origen as a stalwart son of a martyr, trainer of martyrs, and near-martyr himself, he could be enlisted as anēr ekklesiastikos into the Church History, while memories of the Great Persecution were fresh, as a one of the church’s prominent public heroes for the benefit of readers in the early fourth century.

To Eusebius we owe the preservation of Origen’s works as a collection that other, later Christian philosophers were able to consult and reproduce by making copies of specific works. And likewise, only because Origen quoted Celsus at length to rebut his charges does Celsus' True Logos continue to be available to the present. Did it circulate independently? Not for long. True, it disputed Christian claims to philosophy, slandered the ekklēsia as the province of rubes, children and superstitious old women, and presented the new religious movement as a danger to political stability. In the recent volume Celsus in His World, Sébastien Moret’s overview of the reception of the True Word first considers anti-Christian treatises written after Origen’s work, and argues that Porphyry, Hierocles, and Julian all knew Celsus’s work itself, although the latter two did not necessarily know it apart from Origen’s text. Morlet thinks that Lucian, Marcus Aurelius and Galen might also have known it; but they may simply have held similar opinions that circulated among disdainful pagans. Morlet does think it possible that second-century apologists and Arnobius knew of the True Logos; but he asserts that Eusebius in his Praeparatio Evangelica and Demonstratio Evangelica targeted not Porphyry, but Celsus.

If already by the mid-fourth century, Celsus’ views and observations lived on primarily through Origen, and Origen’s Contra Celsum remained available mainly thanks to Eusebius, how did the Contra Celsum circulate? From the library of Eusebius, who had inherited what remained from Origen’s library when he became bishop of Caesarea, came, most likely, the copy that traveled to Asia Minor; likely the Tura papyrus containing portions of the text originated there as well. What Origen might have thought of Eusebius’ biography and his collection of the library we cannot know, but it seems clear enough that Origen still would have been cautious about bishops per se: before the rise of his episcopal bully, Demetrius of Alexandria, the intellectual leaders of the early Christian communities had been, like Clement of Alexandria, Justin or Tertullian, teachers, not bishops – though sometimes as presbyters, and Origen was the most accomplished of that tradition. As teachers, they had benefited from the philosophical education common to the Mediterranean world in the second century and were able to express the philosophical core – hidden in symbols and obscure stories – of the Greek Jewish scriptures and the New Testament. In this, they were aided by the works of Philo of Alexandria, not only by his exegetical works but by those writings in which he portrayed a Jewish Greek life obedient to Torah and organized as a philosophy largely along the lines of early Graeco-Roman Platonism. Clement had rewritten the works of Philo in places to show how Jewish writings and worship led to Christian anabasis, and Eusebius followed suit: he claimed the Therapeutae as truly Christian ascetical philosophers, and in his Church History claimed Origen as the ascetical teacher of a church at one with empire. Contra Celsum became, improbably, a proof of the high social status of Christianity and in its defense, its ticket to imperial sponsorship. What effect did the hostile attention of Porphyry and Julian have upon the reproduction and use of the Contra Celsum after the death of Eusebius? Perhaps in part, it lay behind Gregory Nazianzus’ attacks on Julian.

The text must have remained available in a library in Cappadocia, because extracts from it had been included in the Philokalia, a text composed by Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nazianzus. It is unknown how the text travelled there, or where it was kept, or for that matter what happened to it after their lifetime. Thought to have been compiled in the 350s or early 360s, it was assembled by the pair of friends in the mountain retreat in which they lived together briefly as ascetics after returning from their schooling in Athens and (in Gregory’s case) Alexandria. Recently, Basil’s part in the work has been disputed; but a letter attests that Gregory in 382 or 383 sent a copy to the bishop of Tyana, Theodore, a hometown friend from Cappadocia, as a typikon of the publication. In the letter, Gregory said that the Philokalia contained “extracts useful to philologoi (people who were “erudite,” or, literally, “fond of discussions”); that it was a response to Theodore’s paschal letter; and that the passages would be a memorial (hypomnēma) for them. Basil and Gregory included only a small portion of Contra Celsum in the Philokalia, of which the first fourteen books deal with scriptural interpretation, and the final eleven with particular topics that, as its editor Marguerite Harl observed, meant to present Christian teaching on such matters as heresies, fate, free will, and evil. The Contra Celsum passages included there would have supported a kind of Christian apology meant, very probably, for well-informed Christians and not for pagan opponents, of whom there were still some in Asia Minor in the last decades of the fourth century.

A final witness to the use of the text is one of the Tura papyri: one of these contains a portion of the Contra Celsum (parts of books 1 and 2) in a papyrus manuscript of the mid-sixth to mid-seventh century, discovered in Tura in 1941 along with manuscripts of Didymus the Blind, now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.[1] The Tura discovery gives some clue to the destination of Contra Celsum in late antiquity. If its first life was a staged, literary version of a courtroom dispute between two Platonists over the validity of the Christian way, its third life was a text likely in a monastic library, then later hidden behind an unused block in a limestone quarry famously used as a British ammunition dump. That the papyrus text came from the sixth or seventh century shows that these two authors were still being read – and read together – in a monastic community that may very well have shared its teaching with visitors from cities in Egypt – who need not have been ascetics of any kind.

Evagrius of Pontus, too, operated a school – and that it was in Kellia does not mean it was isolated or inaccessible to all but monks. As a former student, and then an assistant, to Gregory of Nazianzus, he surely had known Contra Celsum. The main concerns of that book he made his own; like Origen he discussed Christianismos, the Christian way; he grounded it in the careful practice of training in practices of virtue to combat the vices, and the moral perception leading to love and knowledge; and although he politely tipped his cowl to several bishops (at least once sincerely), the basic contents of his teaching came largely from Clement and Origen – and as the sixth-century condemnations would demonstrate, he expanded upon them. Evagrius, too, was vitally interested in the Christian politeia; like Origen, he recognized Judaism as the first instance of the politeia, now extended to the entire world; like Origen he opposed metaphysical dualism and condemned any hatred of the body, and he regarded the anabasis – the return to the original condition of the rational being as mind in communion and unity with the divine One – as the goal of that politeia. The insights of Origen (and Clement) with Didymus and Evagrius, made up, through their adaptation in John Cassian and various Eastern monastic writers, the theoretical basis of the monastic movement and extended a non-episcopal politeia as a parallel track for Christian governance alongside the more familiar structure of priest, bishop and archbishop/patriarch. That some of these later writers (not Evagrius) reduced the voltage of Origen, his Alexandrian predecessors and Cappadocian heirs, does not diminish their contribution to this other Christian form of politeia, the monastic movement, with its constant orientation to prayer, psalmody, the invisible Temple, and the rise of humanity toward its higher and better state.[2]

Thanks to Byzantine scholars, the text and not just the influence of Origen's works, including the Contra Celsum, lived on beyond the late fourth century, despite the local council of Alexandria’s condemnation of "Origenism" in 400 (followed by another conciliar decision in Rome, in 403) which Justinian amplified with more anathemas in the Letter to Menas of 543 and the anathemas publicized after the Second Council of Constantinople in 553, expanding the condemnations to Evagrius and Didymus the Blind. Later councils repeated these decisions.

Yet to some readers during and after Justinian’s reign, the Contra Celsum remained necessary: the sole surviving full copy, the source of all eighteen later manuscripts, originated in the thirteenth-century Greek East, commissioned and copied by whom we do not know. Thus, Origen never left the bloodstream of Byzantine thought. Although some Byzantine authors (Photius, for example, in the ninth century) denounced Origen, the tenth-century Suda borrowed Eusebius' words to praise him, and the larger tradition could not rid itself of Origen's thought – not from theology, and not from liturgical texts; certainly not from the inherited aims of the monastic life. Contra Celsum would not be here to translate had it not been preserved complete, in a Byzantine library where in the Palaeologan period (ca. 1259-1453), it could provide a resource for the defense of Christianity during the advance of the Ottomans and the Byzantine engagement with Muslim philosophers. John VI Kantakouzenos and Manuel II Palaiologos had used it, as had the patriarch Gennadios II Scholarios, though the latter used it critically. One manuscript, brought westward and copied repeatedly in the west, preserved the entire text; Marsilio Ficino used it and introduced it to the intellectual circles of Florence: this is why we have the book today, now in steadily improving editions and in numerous translations since the Renaissance. And because it preserves the views of two Platonists – one Christian, the other anti-Christian – it even exercised an appeal in Puritan Cambridge, to the Platonist John Smith. In their differing twentieth-century translations, Henry Chadwick and Fr. Marcel Borret, S.J., more than did it justice; Joseph Trigg and I have attempted to do the same in the twenty-first, for the demanding, revolutionary, egalitarian Platonist and Christian witness, the genius, Origen.

[1] See Caroline T. Schroeder, “The Discovery of the Papyri from Tura at Dayr al-Qusayr (Dayr Arsaniyus) and Its Legacy,” in Christianity and Monasticism in Northern Egypt (Cairo: American University of Cairo Press, 2017.

[2] See Gerhart Ladner, The Idea of Reform (Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 1959).

Born in Hampton, Virginia, in 1951, Robin Darling Young has taught at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., where she is Professor Emerita of the History of Christianity, and at the University of Notre Dame and Wesley Theological Seminary. Her scholarship has concentrated upon the ascetic and contemplative literature of the Greek, Armenian, and Syriac traditions; most recently she has been chief editor and translator of Evagrius of Pontus: The Gnostic Trilogy (Oxford University Press). Her current project is a study of the thought of Evagrius in his own time, and in its afterlife, as it conveys Origenism into the Armenian and Syriac monastic cultures of late antiquity.