Alex P. Jassen, Violence, Power, and Society in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2025.

My first exposure to the intersection of religion and violence was watching the conflict between the Branch Davidians and United States government agents unfold on national news in 1993. The Branch Davidians were a millennial group living in a compound known as the Mount Carmel Center near Waco, Texas. They were led by a charismatic leader with a uniquely messianic name and self-consciousness – David Koresh. Similar to so many others, I watched this story with curiosity and quite a bit of confusion. Who exactly was this group with a biblical sounding name? How long had they been in existence and why did the encounter with the government agents turn violent so quickly? Along with others, I learned about the Branch Davidians from the media, which was woefully unprepared to explain the origins of the movement and how its millennial and apocalyptic orientation fueled the present moment. These concepts were unknown to most onlookers. Most simply regarded the Branch Davidians as a cult – and like all cults, characterized by violence.

Over two decades later, I found myself returning to the story of the Branch Davidians as I began a research project related to representations of violence in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Whenever I would describe my project, conversation partners would routinely bring up the Branch Davidians – or perhaps depending on their age or geographic setting, the People’s Temple, Heaven’s Gate, or some other religious group whose identity is known because of the way in which highly violent encounters with insiders or outsiders brought them to public attention. The more I examined this juxtaposition, the more I became convinced that it was more than merely a conversation starter. Scholars from multiple disciplinary perspectives have built a robust field of study of New Religious Movements (the preferred term now). A large part of this conversation has focused on the role of violence in these movements, in particular trying to understand why some movements turn violent while the overwhelming majority do not. I learned that the Branch Davidians had a long history as a breakaway movement of the Seventh-Day Adventists and spent most of their history as a protest movement in conflict with the social order. Violence as an idea often infused their ideology – especially their eschatological imagination – but violent confrontation with insiders and outsiders was the exception. Scholarly research on the Branch Davidians explores the internal and external factors that increased volatility in the group and precipitated a shift from contestation to violence. The more I examined the scholarship, the more I became convinced that cross-cultural representations of religion, power, society, and violence offered the analytical lens I needed to make sense of violence in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

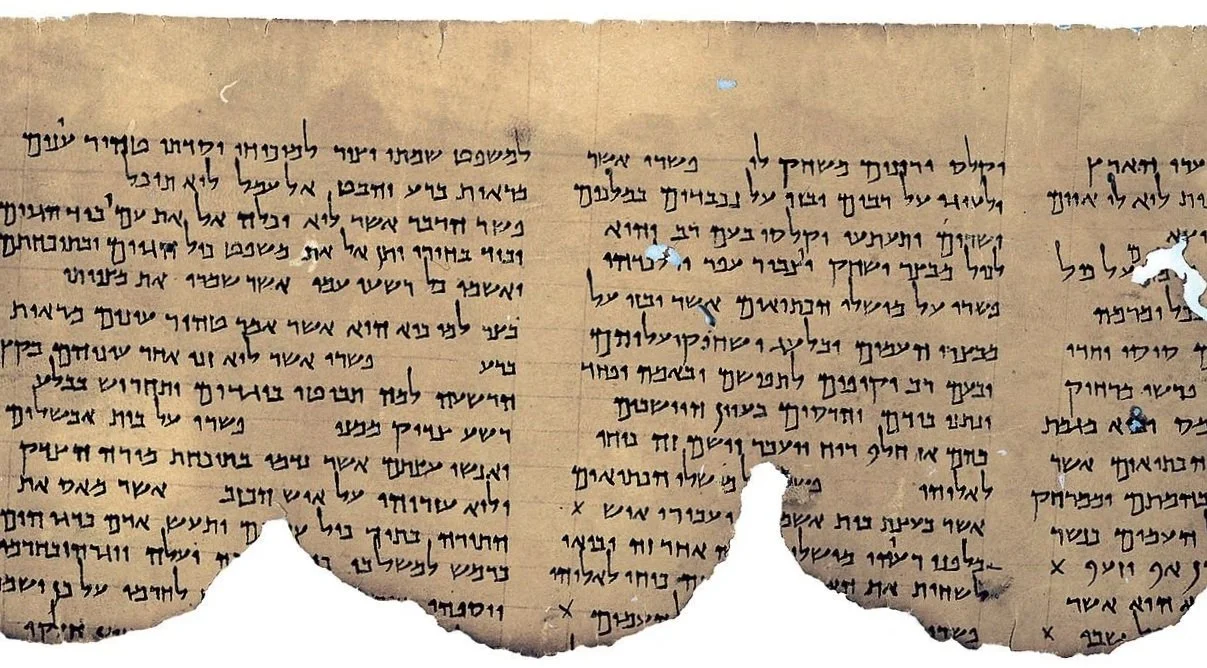

Violence is a key theme in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Jews in the Second Temple period experienced several instances of violence – both as perpetrators and as victims – and the Dead Sea Scrolls contain many traces of this lived reality of violence. Yet the writings of the group associated with the Dead Sea Scrolls reflect primarily a world of imagined violence. Violence against this group’s enemies frames a large part of their vision of the end of days. The War Scroll, for example, describes an end-time holy war, which would inaugurate the final period of the end of days and result in the complete annihilation of all forces of the Sons of Darkness, consisting of non-sectarian Jews and foreign enemies. The Sons of Light – the Dead Sea Scrolls Sectarians – would be led in battle by the angels and God, whose military power guarantees victory. This expectation of the violent destruction of the enemies in the eschatological age is balanced by a policy of nonviolence against the opponents in the present time. Violence is always deferred to the eschatological age and explicitly avoided in pre-eschatological time.

In pre-eschatological time, the Dead Sea Scrolls Sectarians imagine themselves as perpetual victims of the empowered others. Pesher Habakkuk famously describes an incident in which the Wicked Priest pursued the Teacher of Righteousness on the Day of Atonement in order to destroy him. Other Pesher texts share versions of this narrative of victimhood: Pesher on Psalms indicts the Wicked Priest for trying to kill the Teacher of Righteousness. It is not just the Teacher who is imagined as a victim. Rather, the texts cast the entire history of the Dead Sea Scrolls Sectarians as one of persecution and victimhood. In all these settings, violence is a carefully constructed rhetorical concept that exists primarily in the imagination of the sectarian authors. Moreover, even this imagined conceptualization of violence is not ubiquitous in the Dead Sea Scrolls corpus. Many texts are infused with a strident “us vs. them” ideology that is so characteristic of the writings of the group behind the Dead Sea Scrolls, yet entirely devoid of any violent expectations, whether against the sectarian enemies or imagined as directed at the Dead Sea Scrolls Sectarians. Social conflict and contestation exist in settings where no violence – real or imagined – is present.

My goal in this book is to understand why the idea of violence functions in these diverse ways in the Dead Sea Scrolls. This inquiry is animated by four big questions that function as the intellectual guide for this book: (1) How do we make sense of the divergent presence of violence in the Dead Sea Scrolls whereby some texts that reflect the deeply rooted antagonism between the creators of the Dead Sea Scrolls and their opponents have no traces of violence, while others are replete with violence? (2) Why do the people behind the Dead Sea Scrolls pursue a seemingly pacifistic stance toward their enemies in the present but simultaneously construct a vision of the utter devastation of these enemies in the eschatological age? (3) Why is violence in pre-eschatological historical time always depicted as perpetrated by outsiders and in such a way in which the people associated with the Dead Sea Scrolls are portrayed as perpetual victims of persecution? (4) What is at stake in the way that violence is almost always depicted in imagined ways in the Dead Sea Scrolls?

In the first half of the book, I situate the sectarianism of the Dead Sea Scrolls in sociological terms. I argue that the group behind the scrolls should be understood as a sectarian protest movement in tension with the dominant social order. But, conflict and violence are not the same thing. I draw on scholarship on New Religious Movements that examines escalating tension and how a complex mix of internal and external factors contribute to the emergence of violence. The comparative framework of New Religious Movements helps explain how the unified collection of the Dead Sea Scrolls contains seemingly incompatible ideologies of violence and non-violence. This collection was created, crafted, and curated over time. The different individuals and groups responsible for this process were responding to ever-changing social conditions. Following this line of analysis, I demonstrate that violence is not a universal part of the ideology of the Dead Sea Scrolls Sectarians. Rather, as with the Branch Davidians and similar movements, it develops alongside the sectarian identity of the group behind the Dead Sea Scrolls.

In the second half of this book, I turn to the role that violence plays in this developed sectarian identity. The Dead Sea Scrolls Sectarians crafted their texts in order to make sense of the world around them and imagine a world that more closely matched their expectations. Here, I engage with a second comparative framework: the broad constellation of ways in which medieval and modern Serbian culture makes sense of its history and imagines its future. In particular, I examine the various ways in which a pervasive sense of disempowerment emanating out of the fourteenth-century Battle of Kosovo shapes so much of Serbian historical narrative and literary imagination. In a similar way, the Dead Sea Scrolls Sectarians responded to their sense of disempowerment by magnifying the power of others while simultaneously underscoring their own narrative of victimhood. This narrative of victimhood transformed the indifference of their enemies into a myth of perpetual persecution. I draw on research in social psychology on collective victimhood and historical memory to ask what is at stake for the Sectarians in crafting a narrative of victimhood in the way they tell stories about their origins, about their founding figures, and about the ongoing struggles that they face as a community. In this sense, I argue that the stories of the Wicked Priest pursuing the Teacher of Righteousness have little connection to historical realities, but are rather part of a larger master narrative of victimhood.

I then turn my attention to the Sectarians’ portrait of the end-time destruction of their enemies. The depictions of eschatological violence offer insight into how the Sectarians responded to their present overmatched position while simultaneously affirming their status as the elect of God. Reversal, reciprocity, and revenge drive these fantasies. The internal discourse of imagined violence in the Dead Sea Scrolls reverses the power of the foreigners and other Jews and the powerlessness of the Sectarians. The Sectarians are imagined as regaining their rightful position of authority and prestige as their enemies are brought to justice. As a fantasy, it allows the Sectarians to imagine a different world in which their disempowerment and feelings of persecution matter little and in fact will be shortly reversed.

The War Scroll represents the most sustained portrait of this highly idealized fantasy of eschatological retribution. These fantasies are intertwined with many practical elements of the expected imminent eschatological war, seemingly marking a shift from imaginary violence to real violence. I characterize the War Scroll using the language of social anthropologists as a violent imaginary. Violent imaginaries represent a process of thinking about how the future violence will unfold. In so doing, the future performer of violence legitimates and justifies the violent action. Building on this conceptualization of imagined violence, I suggest that the War Scroll should best be understood as a propagandistic tool to prepare the Sectarians as they inched closer and closer to what they believed was the imminent end of days and the eschatological war.

The Dead Sea Scrolls inhabit a world between texts and ideas, between imagination and lived reality. The texts are carefully constructed literary productions that reflect a wide range of human creativity and imagination, and likely a good deal of anxiety about the world and the authors’ place in it. My goal in this book has been to peek behind the texts to recover the opaque world of the ancient people who created these texts and the impulses that compelled them to do so. In so doing, I also was finally able to answer many of my own lingering questions about the Branch Davidians.

Alex P. Jassen is Ethel and Irvin Edelman Professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies and Chair of the Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies at New York University. He is the author of Mediating the Divine: Prophecy and Revelation in the Dead Sea Scrolls and Second Temple Judaism (Brill, 2007), winner of the 2009 John Templeton Award for Theological Promise, and Scripture and Law in the Dead Sea Scrolls (Cambridge University Press, 2014).