Catherine Hezser and Constantin Willems introduce the AHRC-DFG Collaborative UK-German Research Project in the Humanities (2023-26) on Rabbinic Civil Law in the Context of Ancient Legal History.

Read MoreAJR Conversations I Good Book: How White Evangelicals Save the Bible to Save Themselves

Possibilities in the Past: The Challenges and Payoffs of Public Scholarship

In this article, we argue that, despite and precisely because of these real cautions, public scholarship can further three core academic responsibilities: teaching, service, and even research.

Read More2024 AJR Year in Review

Ancient Jew Review is thankful for our community of contributors and readers invested in learning about Jews and their neighbors in the ancient world. For the year of 2024, these are our ten most-read pieces published this year!

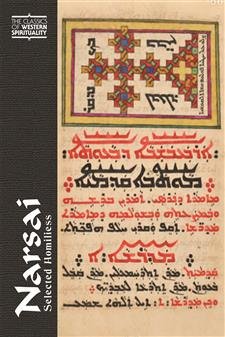

Read MorePublication Preview | Narsai: Selected Sermons

As I learned more about the literature and history of my tradition, I found myself drawn to another important author, Narsai, and wondered whether someday a similarly accessible and instructive volume might be written about him. This project has been both a dream and an aspiration ever since.

Read MoreBook Review | Animal Rights and the Hebrew Bible

Indeed, these audiences in particular would benefit from Olyan’s treatment since they have adopted, at least in part, the academic tools of biblical scholarship, take the Bible seriously as a text of moral significance, and could theoretically affect social and political change in a way that is not limited to academic circles.

Read MoreGuide to Biblical Citations: Teaching Resource

“I came to a realization similar to the one about composition history, though considerably more mundane: the jumble of words, numbers, and punctuation that make up a biblical reference is objectively confusing if you’re not used to it!”

Read MoreBook Review | In the Court of the Gentiles: Narrative, Exemplarity, and Scriptural Adaptation in the Court-Tales of Flavius Josephus

Other Jewish texts are perhaps more difficult to directly compare with Plutarch, yet Edwards’ approach may contribute towards the examination of comparative forms of exemplarity for readers in different ancient Mediterranean cultures and languages.

Read MoreGod’s Monsters: Vengeful Spirits, Deadly Angels, Hybrid Creatures, and Divine Hitmen of the Bible

Esther J. Hamori, God’s Monsters: Vengeful Spirits, Deadly Angels, Hybrid Creatures, and Divine Hitmen of the Bible. (Minneapolis: Broadleaf, 2023).

Friedrich Nietzsche’s most famous aphorism is probably his warning that “he who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster. And if thou gaze long into an abyss, the abyss will also gaze into thee.” In this context, “fight with” ostensibly means “fight against.” The idea is that opposing evil paradoxically brings a person so close to evil that they enter its noxious sphere of influence. However, the preposition “with” is suggestively ambiguous (in English, at least). It could also mean fighting alongside monsters—i.e., on the same team as the monsters. Alternatively, it could mean fighting by means of monsters—i.e., using the monsters to fight. If people who fight against monsters risk becoming monsters, how much more so these other people?

I thought about Nietzsche’s iconic line as I read Esther J. Hamori’s God’s Monsters: Vengeful Spirits, Deadly Angels, Hybrid Creatures, and Divine Hitmen of the Bible. YHWH, the Israelite deity, has a track record of fighting with monsters—i.e., against monsters. For instance, there is Leviathan, the “slippery, twisty serpent” (Isa 27:1) whom YHWH is periodically depicted as skewering. Leviathan has deep roots in pre-Israelite mythology, where he is the master of the sea and the embodiment of the primordial chaos that the sea represented for many ancient cultures. The Bible inherited and transformed a myth in which the high god establishes cosmic order by fighting and defeating this monster. It lurks behind many biblical depictions of creation—including the most famous one, with which the Bible itself begins.

For many religious readers of the Bible—both the Hebrew Bible, which is Hamori’s specialty, and the New Testament—the idea that God created the world by thrashing a creature straight out of Tolkien is probably somewhat unsettling. However, for Hamori, that’s the easy part. While she addresses Leviathan in God’s Monsters, she’s much more interested in the other possible meanings of Nietzsche’s aphorism (though, to be clear, she doesn’t cite him). “The most dangerous of [the biblical] monsters are in God’s employ,” she writes. “They’re not his opponents—they’re his entourage” (p. 8). YHWH, Hamori urges, fights alongside and by means of monsters. And she’s not shy about spelling out the terrifying implication, which makes Leviathan look like a pet goldfish: “This God may be the monster of monsters” (p. 7).

Hamori comes by this interest honestly. Throughout her career, she has shown a notable predilection for what can only be described as the “weird” parts of the Bible—i.e., the parts that challenge the rarified monotheism that many Jews and Christians eventually came to associate with it. Her first book addressed divine anthropomorphism, situating biblical depictions of God as a man in their West Semitic context. Next, she wrote an excellent volume about Israelite women’s divination—a combination of two categories that the Bible’s patriarchal authors typically considered dangerously subversive even separately. In this relief, a book about God’s monsters—and God as a monster—is par for the course.

At the same time, God’s Monsters represents something new for Hamori: it is her first book fully intended for a general audience. Whereas many scholars struggle with this transition, Hamori aces it. She clearly delights in challenging the norms of academic disinterest. (The parallel with her delight in challenging sanitized monotheism is no coincidence.) She tells us with disarming honesty that it was her brother’s death by suicide that led her to the Bible’s “macabre stories” and “their recognition of a troubled reality” (p. 9). She mobilizes instructive anecdotes from her experience as a Jewish professor at a Protestant seminary. And she is consistently, relentlessly hilarious—through both her irreverent authorial voice and her gleeful fluency in the monsters of pop culture. I’ve never seen a Bible scholar set the Good Book alongside the SyFy Channel original movie Sharktopus (2010). And, you know what…it works!

Some readers might find Hamori’s combination of seriousness and frivolousness to be incoherent. However, I would argue that it’s a faithful reflection of what she’s talking about. Monsters themselves are both serious and frivolous. If we aren’t open to this duality, then we’re going to miss crucial dimensions of how the Bible presents God. Hamori’s goal is to encourage that openness. Through its unconventional style, God’s Monsters achieves a profound convergence of matter and form. It’s not just the Bible that is “wild and dangerous terrain” (p. 1). It’s this book too. It’s not just in the Bible that monsters have a “propensity to break into [our] realm” (p. 6). It’s in this book too.

In Part 1, “God’s Entourage,” Hamori introduces us to six of the monsters who do God’s bidding. First, in Chapter 1, we meet the seraphim: winged, fire-breathing snakes whose terrifying form is conveniently obscured behind their transliterated Hebrew name. God deploys these creatures against Israel in order that he might then protect Israel from them, holding out the promise of healing their deadly bites. “This is ‘protection’ in the mafia sense,” Hamori argues (p. 21). She builds toward Isaiah’s famous throne vision (Isa 6), where seraphim ominously herald God’s decision not to heal the people and instead to facilitate their destruction.

Chapter 2 brings us to the cherubim, another obfuscatory transliteration. These figures are known to most in the West as round-faced, winged babies. In reality, they are frightening hybrids of dangerous creatures such as eagles, lions, and bulls, plus (adult) humans (e.g., Exod 25; Ezek 10). Like the lamassu who guarded the Assyrian emperor’s palace, cherubim are heavenly border patrol agents who “prevent passage between [divine and human] realms—in both directions” (p. 29). They are all that stands between Israel and their God’s deadly physical presence. Unfortunately for them, God can tell his bodyguards to stand down when he wants to let loose and, say, destroy Jerusalem.

In Chapter 3, Hamori complicates the regnant picture of Satan. She takes us to a time before his role as the Devil, when he was the Adversary (satan in Hebrew)—God’s close associate on the divine council, essentially a heavenly prosecutor (e.g., Job 2). “For the judge to prod the prosecutor to scrutinize anyone would already be shady,” Hamori writes of God’s permitting the Adversary to afflict the righteous Job. “Here, the judge is deliberately targeting someone he knows to be innocent. This is the very picture of corruption” (p. 84). If Satan eventually becomes the quintessential anti-God monster, his backstory shows that God’s relationship to monsters is always more complicated than such binaries.

Chapter 4 addresses angels. If cherubim maintain boundaries, then angels transgress them; they are “realm-crossers” (p. 109). We usually think of this as a good thing: angels enter our world to help us. Biblical angels do sometimes come in peace. However, just as often, they come to kill (e.g., Gen 19; Num 22; 2 Kgs 19). Far from benevolent protectors with glowing halos and white wings, these angels are shapeshifting agents of divine violence. Hamori notes that when angels show up in biblical narratives, the humans frequently panic. This is because “biblical characters, more often than Bible readers, recognize angels for what they are, and know full well the lethal danger they pose” (p. 106).

In Chapter 5, we meet demons. These are not like the explicitly personified demons famous from the New Testament or, for that matter, The Exorcist (1973). Rather, these monsters “are hidden, masked in natural phenomena and obscured in translation” (p. 140). These include pestilence and plague, who appear as a dynamic duo in a poetic account of God’s theophany (Hab 3). Hamori carefully traces their origins in pre-Israelite mythology. These hidden demons, Hamori warns, “are the demons you should be worried about” (p. 140). By now, it will not be surprising why: in contrast to many of their ancient Near Eastern predecessors, the biblical versions take their marching orders from God.

Finally, Chapter 6 gives us mind-altering spirits, God’s go-to when he wants a subtler touch. Basically, they are weapons of psychological warfare. Saul (1 Sam 16) provides the textbook example: “God … sends the evil spirit to terrorize Saul as reprisal for his disobedience. … Saul’s downfall is a slower process, sparked by the effects of the evil spirit dismantling its victim, never ending until Saul is in the ground” (p. 180). If the image of God working behind the scenes has often been a source of reassurance, then evil spirits, Hamori urges, show us that these covert activities are not always benevolent.

In Part 2, “The Monsters Beneath,” Hamori shifts to creatures whose relationship to God’s authority is more complicated. Chapter 7 takes up the famous monster whom I mentioned earlier: Leviathan, a sea dragon with an impressive mythological pedigree. Hamori reviews the familiar places (e.g., Isa 27; Ps 74) where these myths reverberate, with God and Leviathan battling for cosmic supremacy. However, her most interesting point is that sometimes, Leviathan is more frenemy than enemy. God’s painstaking description of the dragon’s wondrous body in Job 41 is tellingly reminiscent of the erotic poetry in the Song of Songs. God admires, even loves his cosmic sparring partner—like Christopher Nolan’s Joker telling Batman, “I think you and I are destined to do this forever” (The Dark Night, 2008). (I suspect that Hamori would approve that, in this comparison, God is the Joker.)

In Chapter 8, Hamori’s tour stops in the underworld. “Ghosts and shades aren’t part of God’s entourage,” she concedes, “but they do reveal a God-monster dynamic that shows some of God’s more troubling interpersonal tendencies” (p. 227). While many people think of the afterlife as something that God is intensely invested in (for better or for worse), Hamori shows us that in the Hebrew Bible, God’s main attitude toward the dead is apathy. Biblical characters fear Sheol, the predominant biblical term for the underworld, in large part because it means being alienated from God (e.g., Isa 38; Ps 6)—although, based on what we’ve seen, we might reasonably wonder if that is really so bad.

Chapter 9, the end of Part 2, addresses giants—sometimes referred to by the enigmatic Hebrew term “nephilim.” Hamori focuses on the giants who supposedly populate the promised land before Israel conquers it (Num 13). “These giants aren’t monsters,” she objects. “They’re human beings who have been monsterized. And specifically, they’re foreigners” (p. 254). If most of God’s Monsters challenges us to see the monstrous in what we have come to regard as benevolent (e.g., angels), then this is the one place where Hamori does the opposite: she urges us to see the humanity in what we have come to regard as monstrous—and to question this “monsterizing” impulse.

Part 3, “The God-Monster,” consists of a single chapter that doubles as a conclusion to the book. By this point, the monstrousness of the biblical version of God is no longer a revelation; it has been reinforced in every chapter. Hamori briefly covers God’s own monstrous traits: he is enormous, he blasts fire, he can shapeshift. “In the Bible’s ancient context, it makes sense that God is a monster,” she observes. “The divine and the monstrous are all intertwined in mythology from this region” (p. 267). She closes with a plea that readers see this as an invitation to a deeper, more sophisticated relationship with the Bible: the God-monster may help us to understand and to navigate our objectively monstrous world.

For all the monsters that Hamori surveys, there is one who plays a surprisingly minor role in her book: us. Human beings mostly appear in these pages as the hapless targets of God’s monsters, not as agents of monstrousness themselves. (Her critique of the monsterization of “giants” is the one clear exception.) Hamori, of course, would scarcely deny that the people in the Bible often do monstrous things. However, she might reasonably object that she doesn’t need to belabor this point because it’s not news to her intended audience. What’s probably more surprising to them is the idea that the God in the Bible does monstrous things—by means, no less, of literal monsters such as fire-breathing snakes and shapeshifting angels.

Fair enough. However, the monstrous people that I have in mind are not the ones in the Bible. They are the ones who wrote the Bible. While almost no one in God’s Monsters is safe from Hamori’s brutally honest lens, she has a striking soft spot for the biblical authors—like God waxing poetic about Leviathan. To see this, it’s worth quoting at length from her conclusion:

The Bible is a compilation of countless people’s diverse perspectives from different places and times. Some of these perspectives complement each other, and some conflict—and the Bible is all the richer for it. … This complexity is part of what gives the Bible its depth and dimension. … The biblical texts that depict God’s deployment of monsters and exhibit God’s own monstrosity give room for our grief, anger, and protest. … How poignant it is that many of the Bible’s ancient writers didn’t pretend that everything would be fine if people would just trust God. Sometimes, they said, God is why things aren’t fine at all. … The Bible isn’t a solution to the struggles of life, but a reflection of them (pp. 269–71).

I wholeheartedly agree with this approach; it is, indeed, what draws me to the historical-critical study of the Bible in the first place. Yet I cannot help but wonder: If Hamori’s point is that God is a monster because he controls the other monsters, then aren’t the biblical authors also monsters because they control the God-monster? After all, the Bible doesn’t simply “reflect” the messiness and suffering of the world. The Bible also constructs such a world—often approvingly, taking God’s side and endorsing the resulting carnage, as Hamori acknowledges in the case of the giants. Sometimes, when the Bible depicts God unleashing his monsters on those who, from our perspective, might not deserve it, you can almost hear the biblical authors cheering, “Hell yeah!” This too is one of those “diverse perspectives” that they convey to their readers.

Hamori’s God’s Monsters unflinchingly brings the Bible’s horrors to light. Nevertheless, the book issues its most productive challenge through the horrors that it more subtly leaves in the shadows. The biblical monsters certainly tell us something about the God who deploys them to do his bidding. But that monstrous God in turn tells us something about the ancient people who deployed him to articulate and to enforce their understanding of the world. In so doing, that monstrous God tells us something about us—i.e., us as people in general, but perhaps especially us as people who cherish the Bible itself, whether as a historical artifact or as a living scripture (or both). In God’s Monsters, Hamori pushes us to gaze into Nietzsche’s proverbial abyss. True to form, it gazes back.

Ethan Schwartz is Assistant Professor of Hebrew Bible at Villanova University.

Exhibition Review | Elephantine: Island of the Millennia

Aramaic marriage document from Elephantine, dated 3 July, 449 BCE, currently at the Brooklyn Museum. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Aramaic marriage document from Elephantine, dated 3 July, 449 BCE, currently at the Brooklyn Museum. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The desire to construct harmonious pasts selectively highlights only those aspects of ancient identities and experiences that align with current ideals, conveniently omitting the less contemporarily palatable. This selective narrative fosters the belief that coexistence is inherent and natural, rather than a hard-fought process.

Read MoreAncient Jew Review: The First Ten Years

Ancient Jew Review Founding Editors (L to R): Simcha Gross, Nathan Schumer, Krista Dalton

Ancient Jew Review Founding Editors (L to R): Simcha Gross, Nathan Schumer, Krista Dalton

Advisory Board member Andrew Jacobs reflects upon the past 10 years of Ancient Jew Review.

Read MoreSeder Mazikin: Law and Magic in Late Antique Jewish Society

As scholars continue to investigate the bowls from multiple angles – paleographic, onomastic, linguistic, social historical, legal, literary, ritual, visual, gendered, comparative – our understanding of Babylonian Judaism and late antique society will continue to develop. Manekin-Bamberger’s insights about the bowls’ contractual dimensions and the professional scribes who produced them – as well as about the overlap of law and magic on a broader scale – are an essential contribution to this field, and will no doubt shape, methodologically and historically, how future studies approach this corpus and its relationship to other ancient Jewish texts and artifacts and to the long history of magic, law, and religion.

Read MoreAuthor Response: Review Forum Yael Fisch's Written for Us

After Echoes of Scripture, very few studies that stemmed from a NT context ever mention rabbinic literature anymore. My book works to revive and reframe this conversation, make room for early rabbinic texts in the study of Paul and make room for Paul in the study of ancient Midrash, without collapsing these texts into constricting and antiquated models of dependency and borrowing.

Read MoreDoes Paul Give Preference to an Oral Nomos over the Written Nomos in Romans 10 for the sake of the Gentiles? A Response to Yael Fisch

“All this to say that Paul’s emphasis in Romans 10 on speaking and subsequently hearing—orality—is not because it is relevant only to his gentile communities, but because it serves as an explanation for why part of Israel still not has yet believed; they cannot believe because they cannot “hear” the oral nomos speaking about Christ and righteousness by trust. “

Read MorePauline Christcentric Hermeneutics

Studies that seek to build on her path-breaking work in the history of midrash will have to pay closer attention to this fundamental X-factor in Pauline hermeneutics.

Read MoreMidrash, Paul, and Difficulty

"We tend to think about rabbinic interpretations, like midrash, arising from a difficulty in the text itself: smoothing out a piece of grit until, in the famous analogy, it becomes a pearl. What if, however, difficulties that arise from the juxtaposition of two texts are fertile ground for interpretation as well—and that interpretation is not meant to make them easier, but rather, harder?"

Read More2023 SBL Review Forum for Yael Fisch's Written for Us

The 2023 Society of Biblical Literature's review panel for Yael Fisch, Written for Us: Paul’s Interpretation of Scripture and the History of Midrash.

Read More“The Art of Comparison: Yael Fisch’s Written for Us: Paul’s Interpretation of Scripture and the History of Midrash”

"After reading Fisch’s book I am convinced that Paul’s general hermeneutic should not be identified as a radicalization of Alexandrian allegory, or as allegory at all. And I can accept, based on Paul’s blend of the intertextual method featured in later rabbinic midrash with the terminology and content of allegory in Gal 4, that allegory and midrash are not always diametrically opposed, at least for Paul. Nevertheless, as Fisch herself recognizes and details, allegory and midrash differ in numerous ways. Moreover, they are not blended in the vast majority of works of ancient Jewish interpretation or in rabbinic literature, which suggests that their distinction as hermeneutical systems has heuristic value."

Read MoreMapping the Sky: Roman Augury in the Classroom

Figure 1: Unrecorded Artist, “Relief plaque with Vulture and Cobra on baskets; falcon on opposite,” 400-30 BCE, limestone, Egypt, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC, NY (CC0).

Figure 1: Unrecorded Artist, “Relief plaque with Vulture and Cobra on baskets; falcon on opposite,” 400-30 BCE, limestone, Egypt, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC, NY (CC0).

"Although we might not have faith in these beliefs today, I have found that while teaching my Roman Empire class, having students reconstruct these fastidious rules, in order to learn to engage with the ars of divination, can provide them with deeper access into Roman beliefs about communication with the gods."

Read MoreDissertation Spotlight: Rethinking Ancient Jewish Politics: The Hasmonean Dynasty in the Seleukid Empire

Was imperial rule indeed so antithetical to local agency, or was it in fact a facilitating factor in the formation and consolidation of local elite identities? Did the Hasmoneans and their supporters really espouse such an anti-imperial political theology as is often associated with them? What would change in our understanding of emerging Judaism and the Jewish political imagination if we were to reimagine the Hasmonean period without such a heavy emphasis on Jewish national and religious identity in opposition to empire?

Read More