EDITING THE MASORAH[1] OF THE MANUSCRIPT BH MSS1 (MADRID, COMPLUTENSIAN LIBRARY)

A text cannot be edited without a proper description of the manuscript that contains it. Therefore, before explaining the criteria followed in the current edition of the Masorah of the manuscript BH Mss1 (M1), I would like to introduce to you briefly this exceptional manuscript.

1. Manuscript description

The manuscript M1 consists of 340 unpaginated folios and contains the whole Hebrew Bible except for the folios which contained Exod. IX 33b- XXIV 7b.[2] It is written in a Sephardi hand and according to the note of purchase found on f. 334v (fig. 1)[3], it was bought by R. Yishaq and R. Abraham, both doctors, in the year five thousand and forty of the creation of the world, 1280, in Toledo.

This manuscript is also known to be the one used extensively as a basis for the Hebrew text of the Complutensian Polyglot Bible edited by Ximenez de Cisneros in the 16th century (1514).

Each folio has three columns and each full column has 32 lines (fig. 2), except for the poetical portions of the Pentateuch (Exod. 15:1-19; Deut. 32:1-43; fig. 3), Judges (5:1-31), and Samuel, which are written in specially prescribed lines, as well as the poetical books (Psalms, Job and Proverbs), which are distinguished by an hemistichal division.

The text is provided with vowels and the accents. Most of the fifty four pericopes into which the Pentateuch is divided and the triennial pericopes, or sedarim, are respectively indicated in the margin by the word פרש and the letter samech, and are sometimes enclosed in an illuminated parallelogram. The division of the text into open and closed sections is exhibited by the prescribed vacant lines, indented lines and spaces in the middle of the lines.

The Masorah parva (Mp) annotations occupy the outer margins and the margins between the columns. The Masora Magna (Mm) annotations are given in three lines in the upper margin and in four lines in the lower margin of each folio. The manuscript has a huge number of Masoretic annotations in figured patterns. These annotations have been located in the Mp, the Mm and the sekum, –a short summary with general information that was usually placed at the end of each biblical book. The forms of the figured Masorah are mainly simple geometric shapes, such as triangles, semicircles, zigzags, circles or a combination. Vegetal motifs and, exceptionally, other forms (e.g., a six-pointed star, a house shape, etc.) also appear.

The thirty-seven cases of the big outer lower Mm are an exception in the context of the manuscript. Their designs, elaboration and complexity contrast with the simplicity of the other types (see outer margins fig. 2 and 3).[4]

Besides the Mp and Mm annotations, a number of lengthy Masoretic rubrics are given at the end of the Pentateuch (appendix I), Latter Prophets (appendix III) and Chronicles (appendix IV).[5] They are written in three columns of 32 lines each (fig. 4), as the folios containing biblical text.

Appendix I contains a) the Summaries to each of the fifty-four pericopes giving the sedarim, pesaqim, the number of words, letters, the variations (hillufim) between the Easterns and Westerns, the ketiv-qere and the chronology of the parasha, and b) the summaries to each of the five books of the Pentateuch giving the total occurrences of the information contained in the pericopes.

The so-called appendix III contains seventeen rubrics considered by some scholars as part of the Dikduke ha-Teamim.

Appendix IV is composed of three parts very different from each other when taking into account the contents. The first part is the repetition of the end of Appendix III and the continuation of the unfinished list. The second part is formed by three lists with midrashic explanations. The third part collects lists of Sefer Oklah we-Oklah type.

2. The current edition

The edition of the marginal annotations of one text is a long and painstaking work. Due to the way that those annotations work and how they are normally expressed, much labor must be done prior to the realization of the edition. The analysis of the marginal annotations has been done following these five steps: 1. Find the words with a circellus in the folio and the Mp annotation attached to each word; 2. Locate the Mm annotations and the words to which they are attached; 3. Identify the simanîm or catchwords; 4. Confirm if the information given in the annotations is true; 5. Understand the annotations.

In order to fulfill step 4, the marginal annotations of the principal Tiberian biblical manuscripts (Cairo Codex of the Prophets, Or 4445, Aleppo codex, and Leningrad codex) and the major Masoretic lists and treatises[6] have been consulted to check whether they contain any information similar to the annotation.

2.1. Editorial criteria

The major innovation of this edition is that only the Masorah and not the biblical text with which it appears in the manuscript is edited. The team in charge of the edition made this decision arguing that the attested differences between the various Masoretic annotations and the biblical text with which they appear proved that the Masorah is important enough to stand on its own and be edited by itself.[7]

Another important decision made by the editorial team is to transcribe the marginal annotations without any alteration or emendation, resulting in a faithful reproduction of the manuscript. So, when the catchwords are not written exactly the same that the biblical text in the manuscript, they are reproduced as they appear followed by the word sic. The defective and plene spellings have not been taken into account unless they have a direct effect on the Masoretic information.

Those Masoretic annotations which are unclear or impossible to read completely by break or wear of the manuscript are in square brackets in the edited text. The complete information according to one of the main biblical manuscripts and traditional Masoretic compilations is given in one note.

If one Masoretic annotation contains some incorrect information, it is indicated in the explanatory notes. When the information given in one Masoretic annotation does not have a parallel in any other source, this lack is registered in the corresponding explanatory notes.

2.2. Description of the edition

2.2.1. Edition of the marginal annotations

Six volumes containing the marginal annotations from the five books of the Pentateuch and the book of Joshua have been published so far.[8]

Each volume consists of an introduction, transcription and study of the marginal annotations, and two indexes.

The corpus is arranged in entries, each separated by three asterisks.

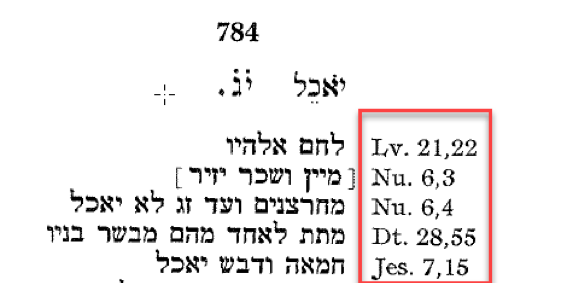

Each entry may consist of: 1) lemma (to the right) and the chapter and verse number (to the left), 2) the transcription of the Mp and Mm annotations with the identification of the simanim or catchwords when they are given, and 3) the explanatory notes.

1) The lemma refers to each word or group of words in the text which carries a Masoretic annotation, and which is, in nearly every case, marked by a circellus, i.e., a graphic symbol – a small circle – often placed over one word or between two or more words of the biblical text.

In absence of the circellus, this is mentioned in the explanatory notes.

The lemma is reproduced as it appears in the biblical text of the manuscript but without vowels signs and accentuation. Vowel signs have only been used to differentiate similar consonantal spellings which could lead into error. The lemma is provided with accentuation in cases where the annotation is concerned with accented words.

2) This is followed by the transcription of the Masoretic annotations.

On the right-hand side is an indication that the annotation is either Mp or Mm. This indication is followed by the Masoretic annotation as it appears in the manuscript.

The identification of the catchwords, both Hebrew and Aramaic, are given in parentheses. Letters in superscript (Mm and Mp) show whether the word has a Masoretic annotation elsewhere in the manuscript.

The liturgical sections which are marked with the letters, samek, peh or the word parasha in the manuscript are also indicated.

3) The explanatory notes placed at the end of each entry are one of the most helpful tools of this edition. They cover various things: information relative to how the text appears in the manuscript (different hands, lack of the circellus, etc.); information resulting from the process of studying and editing each annotation (if one siman has been repeated or omitted, when an annotation is incomplete, when the information is incorrect, the parallel occurrences in other manuscripts and Masoretic works, etc.); any other necessary information to fully understand each annotation.

Each volume has two indexes at its end: the first one of lemmas in alphabetic order with the exceptions of particles and pronouns; the proper names are listed in the second part of this index. The second index presents a table with the Biblical quotations referred to in the Masoretic annotations of that book.

2.2.3. Edition of the Masoretic Rubrics

For the first time, this kind of Masoretic material has been edited and studied.[9]

The norms followed in the edition of these appendices are, in general, similar to those described for the volumes on the marginal annotations. The corpus is arranged in entries, but because of their varied form and content, the edition of each appendix has its own peculiarities and layout to facilitate its comprehension and consultation.

Appendix I

The text is arranged in three columns: the lemma of the information (sedarim, parasiyot, etc) followed by the corresponding number, when it appears in shortened form, is placed in the first column. But if the number is not given in shortened form, it is placed in the second column. The simanim are placed in the second column. And their identification appears in the third column.

The parasiyot are referred to in the manuscript by the mnemonic siman instead of by their names. In the edition, the name of the parasha and the verses it comprises have been added into square brackets.

Appendix III

The text of this appendix continues apart from the simanim and their identification which are arranged in two columns.

The comparison of the content of this appendix with the most significant sources has shown that the text of M1 is original in its final form, with elements of the four sources consulted as well as others of its own. Thus, to appreciate better these differences and similarities, the complete text of the sources is offered in an attachment placed immediately after the appendix.

Both texts, the appendix and the attachment, appear underlined: a) the text of the appendix when it is not corroborated by any source, and b) the text of the sources when it is not similar to the M1’s text. A number in square brackets is placed at the beginning of each list in the text of the appendix. In the attachment, the sources used to check each list have the same number.

Appendix IV

The three parts that form up this appendix have each own layout.

For the first part, which is the repetition of the end of Appendix III and the continuation of the unfinished list, the layout for Appendix III is followed: the text is continuous, apart from the simanim and their identification which are arranged in two columns.

For the second part, that is the three lists with midrashic explanations, the heading is separated from the rest of the text.

For the third part, with lists of the Sefer Oklah we-Oklah type, the heading is separated from the information which is arranged in three columns. The first column has the word which relates to the information or, in some cases, one word representative of the siman. The simanim are placed in the second column and their identification in the third one.

The translation of the headings into Spanish is given in square brackets at the beginning of each list.

The words related to the phenomenon ketiv-qere are usually written in the manuscript according to the ketiv. If those words are written according to the qere this is registered in the corresponding explanatory note.

Two indexes are placed at the end of this volume: the first one of lemmas and the second one with the biblical quotations. The index of lemmas is formed by three different lists, one to each appendix. In the index of Appendix I the names of the parasiyot and the summary of the books of the Pentateuch are pointed out. In the two other indexes the headings of the lists are pointed out, arranged in alphabetical order.

Dr. Elvira Martín-Contreras is Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Languages (CSIC).

[1] The technical term refers to the annotations that appear next to the consonant text of the Hebrew Bible in the margins of the so-called Masoretic codices. See A. Dotan, “Masorah”. In Encyclopaedia Judaica. Second Edition, vol. XIII, 614.

[2] Digitized version: http://dioscorides.ucm.es/proyecto_digitalizacion/index.php?doc=5309439296&y=2011&p=1

[3] All the images of the article belong to BH Mss1 at the Biblioteca Histórica Marqués de Valdecilla. Reproduced with the permission of the Biblioteca Histórica Marqués de Valdecilla.

[4] E. Martín-Contreras, “The Image at the Service of the Text: Figured Masorah in the Biblical Hebrew Manuscript BH Mss1” Sefarad 76 (2016) 55-74.

[5] For a complete description of these material cf. E. Martín Contreras, “M1’s Masoretic Appendices: A New Description,” JNSL 32 (2006), 65-81.

[6] F. Díaz Esteban, Sefer Oklah we Oklah (Madrid: CSIC, 1975); A. Dotan, The Diqduqé hatteamim of Aharon ben Moshe ben Asher, with a Critical Edition of the Original Text from New Manuscripts (Jerusalem, 1967); S. Frensdorff, Das Buch Ochlah W’Ochlah (Hannover, 1864); C. D. Ginsburg, The Massorah Compiled from Manuscripts Alphabetically and Lexically Arranged, With an Analytical Table of Contents and Lists of Identified Sources and Parallels by A. Dotan, 4 vols. (New York: Ktav, 1975); B. Ognibeni, La seconda parte del Sefer Oklah weOklah (Madrid: CSIC; Fribourg: University of Fribourg, 1995).

[7] A. Dotan, “The Contribution of the Modern Spanish School to Masoretic Studies,” Estudios Bíblicos LXVIII (2010), 411-418: 416.

[8] E. Fernández Tejero, Las masoras del libro de Génesis. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid: CSIC, 2004); M.ª T. Ortega Monasterio, Las masoras del libro de Éxodo. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid: CSIC, 2002); M.ª J. Azcárraga Servert, Las masoras del libro de Levítico. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid: CSIC, 2004); M.ª J. Azcárraga Servert, Las masoras del libro de Números. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid: CSIC, 2001); G. Seijas de los Ríos, Las masoras del libro de Deuteronomio. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid: CSIC, 2002); E. Fernández Tejero, Las masoras del libro de Josué. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid: CSIC, 2009).

[9] E. Martín-Contreras, Apéndices Masoréticos. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Textos y Estudios “Cardenal Cisneros,” 72; Madrid: CSIC, 2004)

![Nikos Engonopoulos, Poet and Muse (1938) [Wikimedia].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1597960393283-09LT3VT2ANQA9M5BXHYV/1024px-Poet_and_Muse.jpg)

![Panel from an ivory dyptich of Rufius Probianus, who was vicarius urbis Romae around 400 CE. [Berlin, Staatsbibliothek Ms. theol. lat. fol. 323, Buchkasten].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1592842801661-0Y732O4NHSY6BA17T4WU/Unknown.jpeg)