Yakov Z. Mayer, Editio Princeps: The 1523 Venice Edition of the Palestinian Talmud and the Beginning of Hebrew Printing, Magnes Press, 2022

A modern book is a two-fold object. On the one hand, it’s an object of physical substance made of paper, ink, wire, and glue. It has a solid economic system supporting its production, manufacturing, transportation, and sales. It has a decent weight; it takes up space, covers walls, and contributes significantly to the appearance of a room.

But aside from its physical dimension, we attribute a non-physical meaning to the book, as a transmitter of culture, ideas, and faith, as an object that transcends – and therefore represents – something beyond the material object. It contributes to the shaping of the self, of society, and of religion. Sanctity is attributed to this bunch of glued paper. When certain kinds of books fall on the ground, some people will pick them up and kiss them. We are not observing a mere object, but an object with a metaphysical character.

The question that guided me in writing this book was the origin of this double perception of the book: was this dual nature created by accident or on purpose? When? And by whom?

I started my inquiry by comparing two colophons written in two versions of the same book. Manuscript Leiden Or. 4720 (Scaliger 3) was written in Rome in 1289. It contains the Talmud Yerushalmi, also known as the Palestinian Talmud. This is an Aramaic 6th century legal composition created in Roman Palestine, a parallel document to the much better-known one, the Babylonian Talmud.

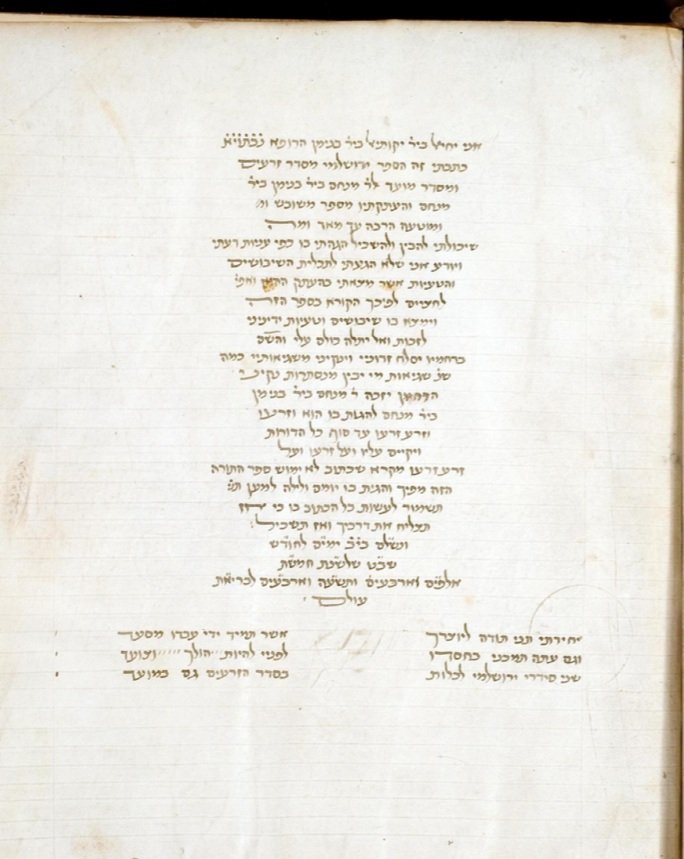

The manuscript was split into two equal volumes, each one concluded with a colophon written by the scribe, Rabbi Yechiel ben Yekutiel, who indicated the exact date when he finished his labor: 12 of Shevat 5049 (1289) for the first volume, and 25 of Adar 5049 (1289) for the second. These are the generic words in which he describes his work:

I, Yeḥiel son of R. Yekutiel son of Rabbi Benjamin, the physician, may his soul rest peacefully and his children inherit the land, wrote this book of the Talmud Yerushalmi … on behalf of R. Menahem ben R. Benjamin. I copied it from a very corrupt and erroneous book. I corrected what I could understand and comprehend, in my humble opinion; I know that I did not correct all of the mistakes and errors I found in that copy, nor even half of them. Therefore, one who reads this book and finds errors and mistakes therein should judge me favorably and not blame me for all of them.

This monumental manuscript, written in beautiful Italian Hebrew script on 674 leaves of parchment, is monumental only to our eyes that have been educated in the age of print. In the eyes of the scribe who copied it, this manuscript wasn’t monumental at all. It was but a corrupted copy of the Talmud Yerushalmi, full of errors and mistakes. It is only one stage in a chain of erroneously transmitted links of the ancient Talmudic text. Rabbi Yechiel thought about himself as being very far from the origin of the text, all he could do was try to correct a few apparent errors, but he would never be able to create a copy of the book “itself.”

The medieval manuscript era ended during the 15th century, with the rise of the printing press’s popularity, and the manuscripts’ role changed from a standard vehicle for transmitting knowledge to an antiquarian object. One example of this changing conceptualization of the manuscript is exampled in the following anecdote.

This manuscript was created in 1289. In the Hebrew year count, it is מט, 49. Pay attention to the small inscription on the bottom of the Colophon page. It is a short calculation, written in Arabic numerals, saying that 283 minus 49 is 234. 49 is the year indicated in the Colophon, the year the manuscript was written. Two hundred eighty-three רפג is another Hebrew year; it stands for 1523. The pen writing these scribbles belonged to someone who lived in 1523, and he was calculating how old this object in his hands truly was.

The Leiden manuscript found its way to Daniel Bomberg’s print-shop in Venice at the beginning of the 16th century, where it was corrected with thousands of annotations; some are just a single letter, others extend to entire paragraphs. This manuscript with its corrections was then used as the source for the first printed edition of the Talmud Yerushalmi.

The calculation in the image above was written by one of the workshop’s printers, who tried to calculate how many years passed since it was created, at the end of the 13th century, until the moment when it reached its final destination, its printing.

In the Colophon of the Venice printed edition of the Talmud Yerushalmi from 1523, a short inscription says:

This is what we found of this Talmud. We made great efforts, sending letters and agents to all places. We ran and exerted, but found nothing but these four orders [the only four Sedarim of the Talmud Yerushalmi]. We engraved them using the lead and iron tool and close scrutiny. We discussed them at length, following the path of truth using good versions, along with three different exact copies that were before us when we proofread this work. We now pray and beg for mercy before the living, most high God, that He cause us to find the remainder of this Talmud and thereby complete this as is fit….

The same manuscript described in 1289 as erroneous and corrupted is now, in 1523, described as an “exact copy.” So what happened in between? What made the medieval scribe evaluate the manuscript as a corrupted copy and the early modern printer to describe this copy as exact? I suggest that the answer lies in a shift in the understanding of the book as a vehicle for information.

To understand this change, I started with a general query about how the printing press was understood in Venice at the beginning of the 16th century. Unfortunately, only a few paratexts from this era were written in Hebrew books, so I went on a short tour in the 16th century capital of print and analyzed some of the introductions Aldus Manutius – the great Venetian printer – wrote for his books. In this short historical window of opportunity, when print was on the rise, most books were printed in a similar process. A medieval manuscript was taken, corrected according to a specific routine, and printed. In my book’s introductory chapter, I tried to understand how a Venetian printer thought about his craft and how he understood his editorial activity. Manutius was a chatty printer, and his lengthy introductions reveal a steady and methodological approach to producing books. He defined the medieval mechanism of manuscript production as one long process of natural corruption. Only the new invention of print could stop this process. Not only could the printing press, in his mind, prevent the deterioration of texts, it could possibly also restore them and bring texts back to their pristine state. For this purpose, a new technique was developed, based on the most up-to-date philological comprehensions of the Florentine academies. At least three manuscripts are taken and compared to each other in a way that enables the corrector to identify and correct medieval mistakes.

Manutius’ introductions are a good window onto the front-end of the Venetian printing press, while the Leiden MS provides a glimpse of its backstage action. A close analysis of the MS reveals the daily life of the correctors and printers working on Hebrew books at the Venetian printing press. The book’s next chapter describes the manuscript, the edition, and the politics of Daniel Bomberg’s printing press. I have identified the two workers who produced the edition. One is Rabbi David Pizzighetonne from Ferrara, a rabbi of Italian Ashkenazic origin. The other is Jacob ben Haim ibn Adoniahu, a young and talented immigrant from Tunisia, who would later produce the most influential edition of the Hebrew Bible in history, and would eventually convert to Christianity and vanish from the stage of history.

The next chapter is a detailed analysis of a significant number of paragraphs from the Talmud Yerushalmi and the editing process of Pizzighetonne. Historians and Talmud scholars are lucky enough that not only the Leiden MS, but another one of the printshop’s manuscripts survived until today. This manuscript covers about a quarter of the Talmud Yerushalmi, it is Ashkenazic in origin, and can be found in the Vatican Library (Vat. Ebr. 133. I have published a codicological and historical monograph of this MS in Hebrew here: https://www.academia.edu/40837003/From_Material_History_to_Historical_Context_The_Vatican_Ebr_133_Manuscript_of_the_Palestinian_Talmud_Hebrew_Full_version ).

A careful comparison of the two manuscripts enabled me to follow the decision-making process that took place in the printshop in great detail. I discovered how the printers defined what an error is in the Talmudic text and how they attempted to correct it. In certain places, I could decipher instances where they “restored” parts of the text even without a proper source. I also identified and described a specific professional—ideological (and religious) disagreement between the Ashkenazic rabbi, who edited the text with an easy hand and a flexible ethical standard, and his young Sephardi fellow, who held a much stricter view of what a corrector can and should do in the text. The next chapter is dedicated to the material level of the book’s production. Jacob ben Haim was in charge of this part – copying the text to letters of lead, combining the text of the first page with the headers, and so on.

Jacob ben Haim worked on the Leiden MS after Pizzighetonne. Thinking he would be the last one in history to work with this manuscript, he used its margins as a personal notebook, filling it with his own writings, blessings, cursings, rhymes, signatures, quotations of biblical verses, and lines of medieval poetry. I tried to understand from these notes how he felt during this period, and found a very lonely man, feeling abandoned in a foreign city and looking for personal redemption (through books? Through Christianity? Through a lover? Who knows).

The concluding chapter returns to the fundamental questions I started with about the nature of the printed book. I tried to compare some medieval conceptions of the book with early modern ones, and I did so by comparing Jewish reactions to the medieval burning of the Talmud in 13th-century Paris with the responses to the early modern burning of the Talmud in various Italian cities in the mid-16th century. In the first case, manuscripts were set on fire, and in the latter – printed volumes. I found it puzzling that the medieval mourners emphasized the national insult, the economic loss, and their wrath, but never mentioned a loss of knowledge. For example, in his famous lament, Maharam of Rothenburg writes:

O You who are burned in the fire, ask how your mourners fare,

They who yearn to dwell in the court of your dwelling place.

They who gasp in the dust of the earth and who feel pain,

They who are stunned by the blaze of your parchment[1]

But in the early modern world, a different tone is heard from the people whose books were destroyed. In the eyes of this early modern generation, the loss of these printed books does equal a loss of knowledge. For example, the Italian poet Mordekhai baby Judah Blanes wrote:

What would we eat without Seder zera‘im

necessary for all these who browse in the Torah

And how would we be happy without Mo‘ed and Nashim

who will give perfume in our noses

Who could be wise without Seder neziqin

who will judge and who will understand the right idea.[2]

How strange that in a period when copies of the Talmud were easier to produce and more numerous than ever, they should be concerned about how they would study now that the books were being burnt!? This counterintuitive indication was found in every place I looked. I knew this discrepancy couldn’t be a question of volume, of how many Talmudic texts had the chance to survive. It is much easier for a printed text, which exists in hundreds of copies, to survive than a unique medieval manuscript. The reason, therefore, cannot be a logical question of probability, but some more profound intuition, about the perception of the printed book and the way 16th-century people thought about books and knowledge.

My suggestion is as follows: I opened the book – and also this review – with a comparison of the Leiden MS colophon, which stated that the text within is a corrupted copy of the Talmud, on the one hand, and the colophon of the printed text, declaring that this very text was accurate, combined from “three different exact copies that were before us when we proofread this work.” In medieval times the material manuscript was considered a temporary materialization, a mere imperfect shadow, of a perfect metaphysical text. Therefore, destroying the material manuscript, while upsetting, could not harm the metaphysical text. In the early modern world, on the other hand, a considerable effort was invested in creating a book that would be as close as possible to the “true” metaphysical text. Many manuscripts were consulted, and hundreds of hours were spent scrutinizing these texts, in an attempt to transform the metaphysical text into a physical object. This economic, cultural, and religious process is what I tried to describe in my book, and the result of this process finds expression in the changed reaction to the burning of the printed book. After all, if the printed book is considered the true carrier of the metaphysical text by its readers, and it is set on fire, the text is lost forever.

Every one of us readers of the Ancient Jew Review is undoubtedly aware of the essential modern concept that if we own a book, it is considered as though we know what is in it. We don’t need to learn the whole Talmud, we only need to purchase it and place it on our shelf. We have replaced our memory, our knowledge, with a physical object. This concept is not an accident, it is a well-designed early modern – and modern –approach to consumerism, developed on purpose, which unifies within the printed book a double character, physical and metaphysical.

[1] (Susan L. Einbinder, Beautiful Death: Jewish Poetry and Martyrdom in Medieval France (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), p. 76. The original Hebrew can be found in Seder ha‐qinot le‐tish’a be‐’av, ed. by Daniel Goldschmidt (Jerusalem: Mosad Ha-Rav Kook, 1972), pp. 135–37, no. 42).

[2] (Avraham Yaari, The Burning of the Talmud in Italy [in Hebrew] (Tel-Aviv: Abraham Zioni, 1954), pp. 47–48, reprinted in Studies in Hebrew Booklore (Jerusalem: Mosad Ha-Rav Kook, 1958), pp. 198–234.)