In an increasingly metrics-focused educational landscape, it can be a challenge to foster creative thinking in students. Students, aware that every grade counts for their future success, tend to avoid risk-taking, even though, as an element in critical thinking, creative risk-taking is a valuable tool in student learning. At the same time, a heightened administrative focus on employability metrics, such as “transferrable skills,” seemingly works to the detriment of humanities programs. To address these issues—namely fostering creative and critical thinking; teaching employable skills; and creating advocates for the humanities—I have adopted and developed an assessment called the UnEssay in a number of my modules at the University of Sheffield.

What is UnEssay?

The ‘UnEssay’ is a creative assignment that helps students learn long-term project management, critical and reflective thinking, analytical writing ability, and a variety of technical skills.[1] Unlike a traditional essay format, which teaches students how to conform to a specific genre and argumentation style and to follow instructions on citation and formatting, an UnEssay gives the learner complete freedom of medium. The content can be communicated in writing, oral performance, multi-media, music, visual art, or any combination thereof. I mark students not on their artistic ability but rather using a short self-analysis of their research and interpretive choices, evaluating whether they have made an effective statement.

The following assignment description appears in my module handbook (semester syllabus):

Assessment: Creative Portfolio

A creative re-imagining, in any medium, of a biblical text.[2] You have complete freedom of form: you can use whatever style of writing, presentation, citation, even media you want. In the past, students have written songs, performed skits, produced art, performed, etc. What is important is that the format and presentation you do use helps rather than hinders your explanation of the topic.

With your creative piece, you must also submit an analysis of no more than 600 words justifying your interpretation, creative choices, and methods.

The 600 word analysis must explain the specific creative, critical, and interpretive choices you made to arrive at your finished product, including theoretical method, text choice, media choice, and scholarship used.

Your creative re-imagining must engage with at least 4 critical, peer-reviewed sources published after 1998. Your analysis must explain the impact of these sources on the finished work.

Depending on the module, the assessment is worth between 40% and 80% of a student’s mark. In all cases, students must submit a proposal of 500-600 words and a proposed bibliography at least 3 weeks before the due date for the final project. Having a written component as part of the assessment allows me to see into the thought process behind the artwork and also alleviates student anxiety about non-traditional assessment methods; the written component gives something familiar for the students to hang onto while freeing up the bulk of their mental energies to think creatively about their projects.

Half-way through the semester, I schedule an hour-long workshop for students to bring in ideas. I ask them to come prepared with a draft outline of their ideas, based on four questions:

What is the topic of your project?

What are you asking about this topic?

What is your answer to your stated research question?

What difference does your answer make for how other people should look at this topic [3]

These focusing questions provide structure for the workshop; students discuss their draft responses to these questions in small groups and brainstorm possible media that would best showcase their ideas. In the final UnEssay workshop, I check in with the students to ensure that the topic is sufficiently narrow, addresses the requirements, and engages with appropriate bibliography. In upper-level modules, the workshop might take the form of formal “oral proposals” where students take 10 minutes to discuss their research question and findings with their peers. Even if the workshop involves only group-work and no formal presentation, I ask students to submit a draft outline of the project, including sample bibliography, thesis statement, and a revised version of the four questions they prepared for the first workshop. This scaffolding supports long-term project management and reassures students about their ability to complete the project.

Results

The resultant projects have included some deeply insightful finished pieces. Not all students achieve very high marks; the range of marks is very similar to the range in traditional assessments like essays and exams. The difference is in which students are at the top of the range: some students who might normally get grades on the lower end of the spectrum because they struggle with formal writing genres or have trouble doing well in exams find that they can manage much higher marks. For those who are used to receiving higher marks based on their ability to write, the UnEssay might highlight the need for developing other skills such as conceptual thinking or concise analysis. Marking UnEssays might seem daunting, but it actually takes much less time, since the written work is only 600 words per student and since you get to know the students’ projects over the course of the semester. I am clear that I do not evaluate artistic talent, but rather creative thinking, care taken, engagement with scholarship, clear articulation of aims and identification of how creative elements support the thesis statement. These are all things we are used to assessing in essays.

Wide-ranging examples of UnEssays I have examined over the years indicate the originality and insight this kind of assessment can produce.[4] For example, student Harry Gold examined the misogynist language used by God in Hosea to speak of Israel as an unfaithful wife; this student composed a song, making use of John Donne’s poetry and taking inspiration from dreamy, sixties-style pop songs that hide abusive romantic imagery in twee vocals. The result lulled the listener into enjoying the short song, while the lyrics and analysis highlighted how frequently domestic abuse is glossed over, both in the biblical text and today.

Another student, Joe Muldoon-Hall, composed a “recently discovered” psalm in fragmentary form. Using square brackets to indicate lacunae in the fictional manuscript (in keeping with scholarly custom), Joe wrote the poem as a literary imagining of Mary’s role as a leader in the early church, from the perspective of a hypothetical first follower, Levi. The literary form allowed Joe to think through the relationship between historical movements and lived experience and literature produced by communities; he used the medium to create distance from a historical Mary or historical Jesus, taking inspiration from actual ancient texts like the Gospel of Mary as well as scholarship.

Another compelling project was a short film by Holly Hardacre. Using scholarly discussions of resurrection, reanimation, and life after death as well as taking inspiration from art history, Holly used film shots of a hand-made figurine of Lazarus, over which she performed a piece of spoken word poetry. Holly focused on the function of eternity and mortality, highlighting the loneliness of Lazarus’s experience, unarticulated in the biblical account. The cinematic technique of filming a still figurine in a variety of settings showcased the passing of time, while the voice-over compelled the audience to search John’s Gospel for Lazarus’s own voice.

Georgina Jessop, “Susanna” 2021

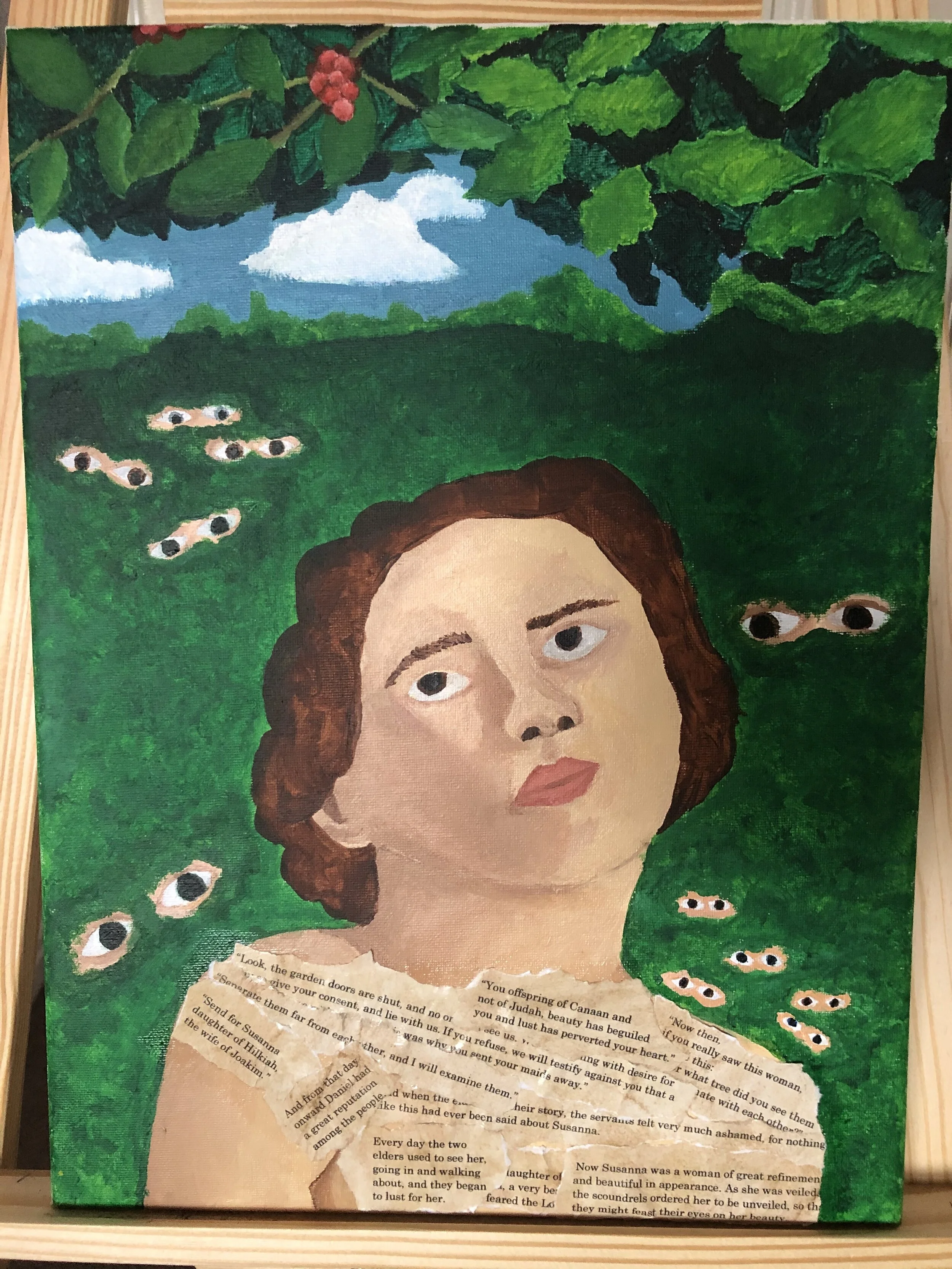

Daisy Ward, “Susanna” 2021

A final example is the use of the Susannah narrative by two students. Susannah is usually very popular as a subject, and previous work has focused on the connections with the #MeToo movement. Georgina Jessop focused on Susanna and sexual violence; she wanted to demonstrate the patriarchal frame that shaped the narrative, a frame that highlights Daniel’s agency rather than Susanna’s. The student commissioned her father to create a wooden frame (she called it a “literal patriarchal frame”), in which she placed an embroidered interactive image of Susanna and other women. The image starts to escape the frame in its three dimensions, allowing the participant-viewer to work around the patriarchal frame of the image and the narrative to engage directly with Susanna herself. Daisy Ward’s work on Susanna concentrated on the topic of the male gaze and voyeurism, in both the ancient text and by commentators. She used paint and collage to apply Caryn Tamber-Rosenau’s and Jennifer Glancy’s work on femininity and male visual pleasure of female subjects to biblical commentaries that feed into male voyeurism and sexualization of Susannah.

Benefits

The creative aspect of the UnEssay assessment fosters student development in three main areas that are of increasing importance to universities: (1) critical thinking skills; (2) the dreaded question of employability; (3) ability to communicate the importance of the humanities to a wider audience. While of course, I hope that my students go on to flourish in their careers after their education, my immediate concerns as a lecturer are fostering student creativity, enjoyment of the module content, and developing critical thinking skills. However, higher education administrators—as well as students and their parents—are increasingly concerned with employability. Pointing out the benefits of creative assessment in terms of employability helps demonstrate to universities as institutions the value of nontraditional assessment to students in addition to the individual benefits to the student.

First, alternative assessments that exercise students’ creativity help students develop a higher level of critical thinking than written essays alone (Sullivan 2015). Creativity has been shown to be fundamental to human cognition, intelligence, and the ability to query information. While writing is an important skill, UnEssays prioritize thinking skills which can be overlooked by students worried about their footnotes and word counts. In addition, the 600-word analysis challenges students to develop clear and concise writing skills,[5] something students often find difficult but easy to sidestep in longer written assessments where more descriptive, rather than analytical, content can be used to take up space (Sheinfeld and Warren 2015).

Second, the UnEssay allows diverse students, including those with disabilities, choice in how to play to their strengths while also supporting students in developing skills for careers outside academia, such as digital media and sound production. This is increasingly important in a higher education landscape whose students come from diverse backgrounds, including mature students, students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds whose previous educational experiences might not match those from elite backgrounds, international students whose cohort might include refugees or asylum-seekers, and other students who might sometimes feel like “outsiders” in the university system (Smith 2016, 88). Flexibility in assessment allows us to respond to changing technological expectations at the same time as it provides options for non-traditional learners to do well in assessment. Students from diverse backgrounds are able to tailor their assessment focus in order to hone skills they identify as important for their future, whether that is journalism, web design, creating legal briefs, art, music, performance, crafting a marketing template, graphic design, sound recording and editing, or anything else pertinent to the students’ specific career goals. Support for technical aspects of the UnEssay are available through my university’s technical support or through the library; in the past I have set up training workshops dedicated to sound editing when a number of students opted to record podcasts. However, aside from these technical tools, students also develop proficiency in self-reflection, a key component of annual reviews in the workplace, for example (McGuire et al. 2009; Green). The self-analysis portion of the UnEssay fosters student evaluation of their own work experience with the aim of improving understanding and future practice, a vital skill since self-reflection is not just key at university or in the workplace, but for student flourishing in general.

Third, students learn how to communicate their findings to the wider public. Aside from the satisfaction and pride students take in their finished work, the communication of research results is valuable to the university within the city as a whole since it allows access to the flood of innovative ideas showcased in students’ research. In my level 3 modules, (and before pandemic times) students host a public exhibit of their UnEssays to allow direct knowledge exchange with the wider Sheffield community. Creating engaged advocates for the humanities sends our students out into the world as our allies; in an environment where humanities faculties are increasingly under threat (Massing 2019), the UnEssay project trains students to communicate not just the content of what they have studied to their communities, but also the creative ways in which they have learned to think. In providing them will the skills to transmit their research into music, sculpture, blog, performance, or whatever other formats they choose, the UnEssay enables short-term and longer-term advocacy for the value of the humanities.

Conclusion

I have been using UnEssays in my teaching since 2016. Student feedback, as well as feedback from colleagues in my department and in Learning and Teaching Services at my university, indicate the value of creative assessment for student learning. Student feedback confirmed that this kind of assessment supported students in developing critical thinking skills: “This was the first module that really made me think!” and “Most intellectually stimulating module in my degree so far!” Students commented that the assessment helped them engage with the subject manner in the way I’d anticipated, and proved useful for learners who found traditional modes of assessment difficult: “As a creative thinker it’s helped with my thought processes rather than being a struggle.”

One key to the success of the UnEssay is the built-in workshopping days. Without structured guidance through this different form of assessment, students can become anxious about whether they are doing the exercise “right”. Because testing-focused learning shapes so much of student learning, especially in the United Kingdom, students often need reassurance that thinking creatively, or outside of the box, will not result in penalization. Workshopping and feedback throughout the process helps students develop confidence in their thinking and ideas at the same time as it fosters that long-term project management skill that we value so highly. It also assists students with skills in both offering and receiving constructive feedback.

The UnEssay is an invaluable tool for fostering critical thinking because it allows a fuller range of creative exploration than essays or exams. Creative risk-taking is integral for student flourishing both within higher education and in the wider workforce. Allowing students to experiment with communicating their ideas in accessible ways facilitates knowledge exchange with the wider public about the value of the humanities. Finally, the benefits of the UnEssay beyond facilitating critical thinking are significant for the current higher education landscape in that the UnEssay also allows students to develop skills that university administrators are increasingly anxious to include in their degree programs to point towards post-graduation employability. But most importantly, the positive student experience and increased engagement work to send forth successful graduates who are in turn future champions of the humanities.

Works Cited

Burke, Alison. 2011. “Group Work: How to Use Groups Effectively.” Journal of Effective Teaching 11 (2): 87–95.

Green, Roxanne. N.d. “Promoting Reflection in the Curriculum.” Promoting reflection in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of Sheffield. Accessed 24 April 2019. https://sites.google.com/sheffield.ac.uk/promotingreflection/home?pli=1&authuser=1

Massing, Michael. 2019. “Are the Humanities History?” New York Review of Books, 2 April 2019. https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2019/04/02/are-the-humanities-history/

McGuire, L., K. Lay, and J. Peters. 2009. “Pedagogy of Reflective Writing in Professional Education.” Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 9 (1): 93-107.

Sheinfeld, Shayna and Meredith Warren. 2015. “Students Think Better with Thinking Pieces: Why You Should Consider Using Low-Stakes Writing Assignments in Your Class.” Ancient Jew Review, 27 May 2015. Accessed 24 April 2019. http://www.ancientjewreview.com/articles/2015/5/27/students-think-better-with-thinking-pieces-why-you-should-consider-using-low-stakes-writing-assignments-in-your-class

Sheinfeld, Shayna. “Genre Bending Writing Assignments.” Association for Jewish Studies. https://www.associationforjewishstudies.org/publications-research/ajs-news/genre-bending-writing-assignments

Smith, Sidonie. 2016. Manifesto for the Humanities: Transforming Doctoral Education in Good Enough Times. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Sullivan, Patrick. 2015. “The UnEssay: Making Room for Creativity in the Composition Classroom.” College Composition and Communication 67 (1): 6–34.

[1] I first read about the UnEssay on Ryan Cordell’s website: https://web.archive.org/web/20201203190303/http://f14tot.ryancordell.org/assignments/unessays/

[2] Depending on the module, there are different requirements for what kind of text students can choose. In ‘Jesus and the Gospels,’ students must pick a text that in some way contributes to the understanding of historical Jesus studies; in ‘Texts of Terror,’ it needs to be a text that the student identifies as troubling or disturbing.

[3] I am grateful to Jonathan Bernier for sharing these questions with me.

[4] All students have given permission for their names and works to be used for this blog post.

[5] Marking the UnEssay based on the self-analysis also cuts down on marking time, particularly in larger classes.