The intended audience for CIIP 5 consists of scholars specializing in the study of early Judaism, early to late antique Christianity, and the early Islamic period. However, given that every inscription is translated into English, non-specialists interested in any of these time periods in this location will benefit from this epigraphic collection.

Read MoreJodi Magness: Retrospective for The Ancient Jew Review

It is my hope that scholars who specialize in the study of texts will recognize that archaeology is not only relevant but indeed vital to their own research.

Read MorePublication Preview | “Listen to the Sibyl”: The History, Poetics, and Reception of Sibylline Oracles

The endurance of Sibyl’s authoritative voice invites analysis by students and scholars interested in gender and antiquity. Throughout the collection's literary, theological, and historical complexities, the one unifying constant is the sibyl herself, an ancient and respected woman prophet.

Read MoreReview | Berkovitz, A Life of Psalms in Jewish Late Antiquity

He moves the question of reception away from strictly exegetical approaches that look for a history of interpretation within a world of ideas, and towards how Jews in Late Antiquity encountered physical scrolls of psalms, how they incorporated them into their liturgical practices, and how psalms played a role in practical religion (e.g., piety and magic).

Read MorePublication Preview: What Animals Teach Us about Families

"One difference between my first book and my most recent one is that this time I let my freak flag fly. My freak vegan flag. What Animals Teach Us about Families is, covertly, a memoir about my becoming a vegan.”

Read MoreSecondary Scholarship: Teaching & Researching in Secondary Education

The sometimes “serendipitous accident” of moving to secondary education can prove to be an enriching, fruitful, and also quite fun experience for academics-turned-high-school-teachers. And while the nature of this work prioritizes teaching and pedagogical development, many academics who have taken it up for themselves have found diverse ways to continue to pursue and publish research.

Read MoreThe Art of Introduction: Teaching Religion in High School

I wish I could say my move to secondary education was grounded in thoughtful reflection or a profound sense of calling that I’d known and honored my whole life. Instead, it was a kind of serendipitous accident that required a big leap of faith. Of course, so are most of the fun things that life sends our way.

Read MoreA Snow Day in the Life of a Classicist Turned High School English Teacher

The relationship between my writing and teaching is different now…. There is a bit more joy in my writing process than there used to be, and that communicates in my teaching. The time I take on a snow day to cultivate my own creative work is good for morale. Writing has always been a positive process for me, but it is especially so now that my professional future in the academy no longer hinges on my ability to quickly and unrelentingly generate monographs and articles.

Read More“Have You Thought About Teaching at a Boarding School?”: An Overview

Another apt turn of phrase for Boarding School Life is: “it is not a difficult job, but it is a demanding one.” But the benefits, in my mind, far outweigh the costs. If you really enjoy teaching, coaching, and mentoring excited and curious young people, this might be an avenue you should seriously consider.

Read MoreSine Qua Non: Teaching Latin in Public School

Secondary-turned academics are indispensable not merely for their banausic training and credentials. At their best, scholars of the humanities embody love of learning and wisdom over mere appearance and sophistry. Where institutions of learning tilt toward test-prep and job training, PhD-trained teachers must fight to keep alive a humanistic appreciation of learning for its own sake.

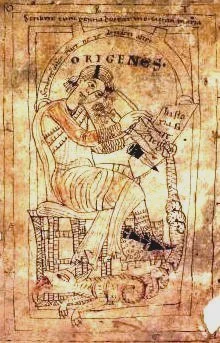

Read MoreOrigen as Political Theologian

In Contra Celsum, Origen deepens this association between incorporeal intermediaries and what we typically classify as constituting the political.

Read MoreContra Celsum as Socratic Philosophy

Origen too imitated Socrates’s example, not least in his approach to rational inquiry. Origen frequently speaks of Socrates as a model philosopher, though he is not above criticism.

Read MorePlato, Politics, and Faith

Joseph Trigg and Robin Darling Young posit the unabashedly philosophical character of Celsus’s challenge and Origen’s response as the basis of their project.

Read MoreIn Defense of Celsus

In this short tribute to Origen and his translators, I suggest that, among much else, Origen shows paradoxically how strong a mainstream polytheist’s case could be against Christianity in the second century, and how even a brilliant apologist could struggle to meet it.

Read MoreA New Translation of Contra Celsum

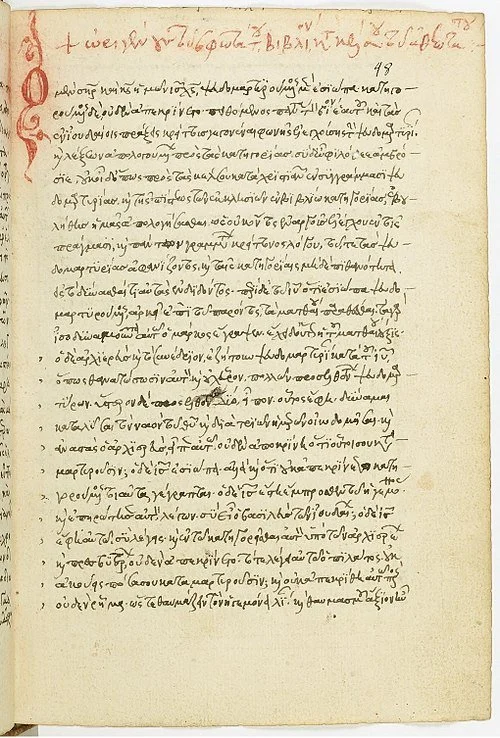

A forum in celebration of Robin Darling Young and Joseph Wilson Trigg’s The Contra Celsum of Origen: English Translation and Facing Greek text (Washington and Cambridge: Harvard University Press/Dumbarton Oaks, 2026).

Read MoreContra Celsum from Caesarea to Constantinople: The Travels of a Byzantine Book

Celsus’ views about empire and cult, whether they were pagan or Christian, were far from dead in the fourth century; they appear in Christian sermons and treatises – not just in their pagan echoes in Porphyry and Julian.

Read MoreOrigen and the Polis: A New Translation of Contra Celsum

Byzantium preserved Contra Celsum because it demonstrated that Christianity was compatible with Hellenism. Renaissance humanism welcomed it because, in doing so, Origen demonstrated that Hellenism was compatible with Christianity.

Read MoreGod's Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible

Candida Moss, God’s Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible. Little, Brown and Company, 2024.

In God’s Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible, Candida Moss expands discussions of slavery in antiquity by uncovering how enslaved persons’ intellectual labor and agency were erased in the production and transmission of the New Testament. Moss demonstrates that enslaved Christians experienced desocialization and depersonalization not only through physical displacement and diminished legal status but also through being textually ghosted: their indispensable contributions were effaced even as they made the very existence of Christian scripture possible. Moss’ work takes up and extends Orlando Patterson’s concept of “social death,” namely the violent uprooting of the enslaved individual from their social and cultural milieu paired with the paradox of being incorporated into their enslaver’s community while being treated simultaneously as nonbeings (1982: 38).

Moss foregrounds the role of the enslaved in the production and transmission of the New Testament, arguing that enslaved laborers were responsible for writing, copying, curating, and publicly reading the texts. In doing so, she challenges prevailing assumptions about solitary (or free) authorship and demonstrates that these contributions, previously erased, must be recognized as acts of coauthorship. For Moss, acknowledging this hidden labor “un-ghosts” the enslaved, granting them visibility and confronting historical harms (p. 265).

Following the Author’s Note and Introduction, Moss structures the book into three principal sections, within which eight chapters are distributed. She then concludes with an epilogue. The first section, “Invisible Hands,” begins with Chapter One, “Essential Workers,” which introduces Tertius, an amanuensis for Paul, who identifies himself in Rom 16:22 as the one writing the letter. Moss does not claim that Tertius composed the entire epistle; rather, she uses Tertius to illuminate the often-erased presence of enslaved and subservient scribes in the production of the New Testament. This chapter demonstrates that many enslavers sent their enslaved children to school to be educated. These individuals often became their enslavers’ scribes, secretaries, librarians, notaries, readers, philosophers, grammarians, and even imperial advisers, such as Tiro, Cicero’s scribe. Moss argues that literate enslaved workers were ubiquitous, and whenever someone in Mediterranean antiquity claimed to be “writing,” they were more likely dictating to an enslaved scribe.

Chapter Two, “Paul and His Secretaries,” highlights Paul’s reliance on enslaved scribes and other servile workers. Notable among these workers are Tychicus, who was with Paul during his imprisonment and may have assisted in composing letters (Eph 6:21); Epaphroditus, who supported Paul during his confinement in Ephesus (cf. Phil 2:25–30); and Onesimus, who likely served as both courier and possibly scribe of the Letter to Philemon. These individuals played crucial roles in the production and transmission of Paul’s correspondences. Typically, after recording his dictation, the scribes would read the letter back to Paul. However, due to the constraints of imprisonment, he may not have had the opportunity to review the final drafts thoroughly, increasing the possibility of errors or ambiguities. Considering their involvement, Moss suggests that Paul’s letters exemplify a form of collaborative authorship—a characteristic not only prevalent in early Christian writing but also common in broader Greek and Roman literary practices. The contributions of these scribes, however, remain largely invisible. This invisibility stems partly from the social stigma attached to reliance on individuals of lower status, and partly from ancient household ideologies that viewed enslaved persons as extensions of their enslavers’ bodies, thereby erasing their agency and labor.

The third chapter, “Rereading the Story of Jesus,” extends the argument that enslaved individuals were coauthors, suggesting that their experiences—particularly in the realm of textual production—reframe the narrative of Jesus. Moss contends that the pervasive structures of slavery deeply shaped both the world Jesus inhabited and the earliest Gospel accounts, making it impossible to separate his story from the realities of enslavement. She urges historians and those concerned with marginalized groups to remain attentive to the presence and influence of enslaved individuals when reading the New Testament (p. 93). Such awareness, she argues, helps illuminate elements of the Gospel narrative—for instance, Jesus’s use of “slavish” speech patterns and his embodiment of traits, which can be associated with an enslaved overseer. His silence during his trial and the degrading violence of crucifixion, Moss suggests, closely mirror the lived experiences of those who recorded and transmitted his story.

The second section, “Messengers and Craftsmen,” explores the often-overlooked roles of socially marginalized individuals in the spread and preservation of Christian literature. Chapter Four, “Messengers of God,” challenges the conventional view that Christianity primarily expanded during the Constantinian era through elite male apostles and intellectual figures. Such a perspective overlooks the critical contributions of enslaved, freed, and otherwise socially disenfranchised individuals. For example, Thomas, in the third-century Acts of Thomas, is sold into slavery by Jesus as a carpenter to Abbanes, while Burrhus, mentioned in Ignatius’ Letter to the Ephesians around 116 CE, served as a key intermediary facilitating communication between the Christian communities in Ephesus and Smyrna. These figures exemplify how enslaved messengers helped bridge the distance between senders and recipients, ensuring not only the physical delivery of letters but also their effective reception.

In the next chapter, Moss shifts her gaze to enslaved copyists who curated, collated, and reproduced manuscripts within wealthy households or in workshops operated by freed-person booksellers. This work required not only technical skill in writing and copying but also interpretive judgment and moral discernment, as copyists had to correct textual errors and inconsistencies while navigating the expectations of patrons and the economic pressures of manuscript production. The agency of these enslaved workers, however, complicates traditional assumptions about the relationships among copying, calligraphy, training, and social status. In this context, a notable mistake in the Lord’s Prayer in the Codex Bobiensis—the earliest Latin Gospel manuscript—offers a revealing example. Instead of “Let your kingdom come,” the manuscript reads, “I have come to your kingdom,” a variation that may reflect something about the manuscript’s production and its producers. Perhaps a bookseller, whether Christian or not, commissioned the codex, or the copyist was an enslaved person in a wealthy household and produced it for their enslaver, thereby leaving subtle but meaningful traces of their presence in the text.

This section draws to a close with a study of how enslaved men and women served as readers. Their oral delivery—through breath, vocalization, pauses, emphasis, and accent—shaped audience reception and interpretation. They not only read the text aloud but sometimes added words or sentences to help listeners better understand what they read and guided them through difficult passages. Accordingly, for Moss, the reader functioned as both a conduit and an author. To illustrate this, she turns to the longer ending of Mark (16:9–20). While agreeing with other scholars who question the status of Mark’s ending as a later development in the textual history of the Gospel, Moss proposes that it is the lector, rather than the copyists or editors, who possibly added the ending.

Part three, “Legacies,” weighs how Roman conceptions of “good” and “bad” enslaved persons shaped the self-understanding of early Christians and interpretations of New Testament texts. Chapter seven, “The Faithful Christian,” analyzes the portrayal of Christians as God’s enslaved and examines the phenomenon of martyrdom in the early centuries. While the concept of enslavement to God has evolved, it continues to rest on the enslaved person's loyalty (pistis/fides) to God as their new master. This dynamic underpins the rhetorical power of early Christian depictions of the enslaved, such as Blandina, a late second-century CE martyr, remembered in the Martyrs of Lyon as recorded in Eusebius’ Historia Ecclesiastica. For ancient readers, Blandina exemplified the ideal enslaved, who were expected to serve, labor, and show gratitude even to the point of death.

The final chapter, “Punishing the Disobedient,” presents Euclea as an archetype of the rebellious and disobedient enslaved person in the second-century apocryphal Acts of Andrew. She was tortured and mutilated by Aegeates, her mistress’s husband. Her story, though fictional, proves emblematic of the violence and mistreatment imposed by enslavers, Christians and pagans alike, on their willful slaves. Moss extends this analysis to Roman carceral spaces, describing their grim conditions: low nighttime temperatures combined with dark and windowless spaces created an atmosphere thick with whistling, weeping, singing, and inarticulate cursing. Moss argues that biblical depictions of divine punishment, such as being cast into hell or abandoned on the streets with gnashing teeth, reflect these real-world experiences of confinement in Roman incarceration and enslavement.

The epilogue highlights the collaborative roles of enslaved and free individuals in shaping the early Jesus movement and the formative centuries of Christianity. It calls for reading the New Testament through the lens of the enslaved, emphasizing their crucial yet often overlooked contributions. Moss asserts that disregarding enslaved laborers fails to address this textual and historical problem. Instead, it merely reinforces and reproduces the ancient enslaving logic of erasure to oppress and dehumanize the most vulnerable.

God’s Ghostwriters provides a creative, eye-opening, and thought-provoking reassessment of ancient evidence, centering the lives of enslaved workers in the writing and dissemination of the New Testament. Through critical fabulation—an act that jeopardizes the status of the event, displaces the received authorized account, and imagines what might have been done or said, borrowed from Saidiya V. Hartman (2008)—Moss reimagines, refocuses, and readdresses the enslaved figures as collaborative authors of the New Testament. The enslaved not only exist in the texts as ghosted figures in the “author’s” hands but also as meaning-makers. With this book, Moss persuasively demonstrates that attending to the enslaved and their labor not only offers a reparative reading strategy for modern readers but also foregrounds their indispensable role in the composition and transmission of biblical and early Christian literature.

Herman Arnolus Manoe is a PhD student in New Testament at Emory University Graduate Division of Religion.

Works Cited

Hartman, Sadiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe Vol. 2 (2008): 1-14.

Patterson, Orlando. Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study with a New Preface. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982.

The Hypothesis of the Gospels

This book draws attention to one important but neglected concept from Hellenistic literary criticism that readers—including Christians—used to organize, describe, and evaluate narrative traditions.

Read MoreThe Poetics of Prophecy Review Forum

Yael Fisch, Karama Ben-Johanan, and Raphael Magarik engaging Raz’s notion of “weak prophecy” in this review forum, with author response.

Read More