“As an occasional series, Unexpected Influences asks scholars to reflect upon one thing outside their respective fields that influenced their scholarship.”

I am going to talk about how music points me toward what I don’t understand about ancient religions, and what I find most interesting in them. Because it has patterns that infuse and shape our communications that go beyond meaning, music exists in the gap between experience and language and provides connections between the two—sometimes startling ones. Yet musical form is also concrete and repeatable, physically present when performed and audible to anyone who cares to listen. This makes it not just mysterious but also comprehensible. While music goes beyond language, we also have language to describe and understand it. And at ritual turning points like the Jewish Day of Atonement, there is a long history of music interrupting or transforming our understanding and expectations of religion.

I Boring Mysteries I went from music to philology but keep wondering about the things music attuned me to that philology leaves out

I have long been torn by the contradiction between the awe-inspiring sweep and power of ancient religion and the boring, sterile style of textual scholarship on it. I was drawn to the idea of uncovering mysteries—prayers from long dead lips frozen in time by an inscription, unseen myths and forgotten ways to see the world. But wait. How do you read that inscription if the language, even the very letters, are a mystery? Decipherment is a grind too, a slow, technical one. And some of the grinding quality of our academic discipline must be directly proportionate to the mystery and challenge of its subject matter.

But is there a point, as the historian Peter Brown suggests, when the technical grind actually takes over and obscures the subject? Brown begins Society and the Holy in Late Antiquity startlingly by declaring that there are times when “it takes a high degree of moral courage to resist one's own conscience: to take time off; to let the imagination run; to give serious attention to reading books that widen our sympathies, that train us to imagine with greater precision what it is like to be human in situations very different from our own.” This is about how I lost and then found something like that moral courage.

I fell into ancient languages almost involuntarily. In college I remember my own surprise at the very existence of a class called “Introduction to North-West Semitic Epigraphy,” taught by someone with the made-up-sounding name of Frank Cross. How on earth could something already so esoteric and ornately specialized-sounding be an “introduction??” I imagined it as a joke, to be followed by “Intermediate” and “Advanced North-West Semitic Epigraphy” or broadened ever so slightly by Introductions to South-West, North-East, and South-East Semitic Epigraphy.

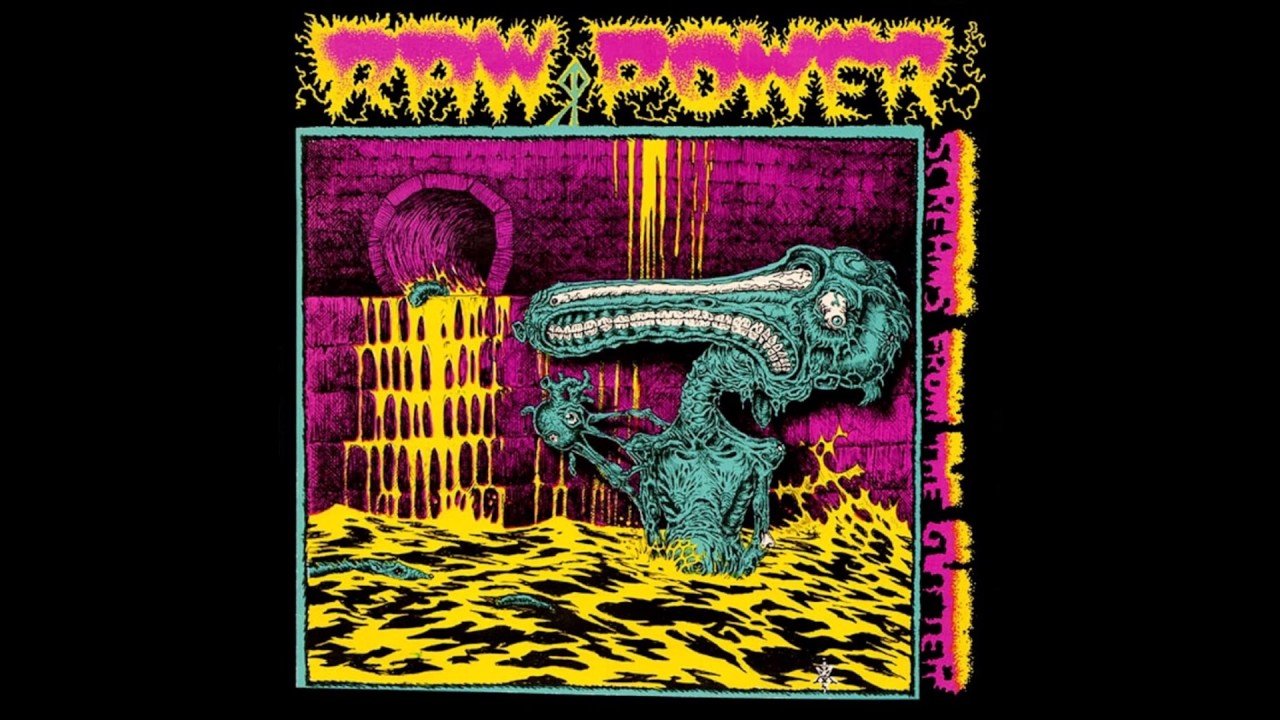

Figure 1: Raw Power album cover

This was all pretty much the opposite of what I liked to do in my spare time: play two-minute-long hardcore songs on the radio by Raw Power, Negative Approach, or the Bags. I liked explosions and was intimidated by the idea of something that just seemed so plodding and hard to learn. I was serious but mercurial, interested in what ideas might crack the world open for me, let me look behind its horrors and absurdities, and cut to the quick of things. Those songs turned my head immediately—sounds from nowhere, the unexpected onrush of a guitar melody, an outraged cry that challenged you to decipher its message.

Was there anything as challenging, as open and searching, in religion as what I heard in music? Unclear. Religion was about tradition and demands—maybe the demands were good but they were old and weird, at once well-known and imponderable (why did the commandments amount to precisely 613? Was that some old men’s idea of a joke?). I’d been introduced to Judaism by a maverick Reform Rabbi, Arnold Jacob Wolf who charmed and bothered my Bar Mitzvah class. A funny, informal, but riveting speaker, Rabbi Wolf projected Judaism’s moral urgency in his sermons, routinely offending our comfortable University of Chicago congregation with his demands to repent from political complacency. No stranger to real-life challenge, he helped start the first pro-Palestinian Jewish political group in America, Breira. When the group was crushed by the Jewish establishment during the 70s, it didn’t seem to quench Wolf’s fire; maybe the opposite.

Figure 2: Rabbi Arnold Jacob Wolf

Rabbi Wolf thought musically enough about the texts that he could make them sing—from jeremiads to hymns. But he thought like a textual scholar too. He was so serious about the challenges and insights scholarship could bring to his traditional texts that he had studied Babylonian with the greatest Assyriologist of the mid-20th century, Benno Landsberger. I was no Landsberger, let alone Wolf, but I did manage to inherit his biblical studies library.

Still, something about Rabbi Wolf’s moral courage—his attunement to the things that haunted and animated the words--stayed with me. Starting out, I couldn’t hear the music in the self-torture of learning ancient texts, an unrewardingly noble calling that I thought I lacked the patience or appetite for. It looked like a workout for the kind of impressive pedant I could never be. Memorizing encyclopedias of trivial details, cataloging and analyzing signs, forms, and texts that I laughed to hear described as “Semitic philology.” Becoming such a text fanatic sounded both numbingly dry and impossibly hard.

Now I’m a Semitic philologist.

II Freeze-Dried Experience philologists also consider the “musical” dimension of prayer as action, but tend to argue by fiat, theorizing that it must have worked

But learning this style of textual scholarship did not make me one of its believers—like Peter Brown I remain acutely aware of philology’s limits. The power of philology is to solve mysteries by narrowing them into data. The Torah is claimed by Jewish tradition to contain limitless significance in each word because it is not just a text but a cosmic entity. Its existence predates the universe itself, for which God used it as a blueprint. But when we philologists talk about what the Torah’s words would have meant to its earliest audiences, our job is to ignore the origins of the universe and limit the discussion to verifiable textual data. We fast-forward from the imagined pre-cosmos to things we can know, the Iron Age and Persian contexts when the Torah’s elements most plausibly first existed. Rather than limitless significance we focus on limited amounts of evidence--the most pedestrian meanings the words had back then--and build from there, bracketing out the rest.

This power of textual scholarship is also its limit: for human beings to have created and used these words, they have to have been rooted in ordinary life and the common artistic conventions of the time. But for human beings to have felt these words, there must have been more to them. What did they hear beyond ordinary life or common artistic convention, and how can we train our imaginations to pick up on it?

There is a melancholy that sets in once we have narrowed everything down to data. Seeing only the words, the precise textual data makes for solvable problems, but leaves out the nonverbal elements that animated it—what you could call the music.

We sometimes try to replace the missing music with sheer theoretical assertion. I am drawn to and have written about theories of performance that redefine texts as events. The idea is that if a prayer or blessing followed the right conventions, it would have turned into an actual event, becoming true by virtue of being accepted. If its formulae were socially acceptable, the texts would be socially real.

Yet such automatic theories of performance risk steamrolling the material as flat as the narrowest philology. Did all ancient speech, properly performed, take on reality like the words of God in Genesis 1:3—“and God said, ‘Let there be light!’ And there was light”? The Priestly writers of Genesis 1 probably did not think so, since they stipulate no regular prayers and almost never depict human ritual language as having any religious effects.

The hypothesis that all the magic really worked appeals to me: maybe everybody who talked about God saw him too. But to simply assume that everybody somehow believed all of it, without asking exactly how or why, is also to abandon the question of what brought this material to life, what animated and explains it, and replace it with a ready-made formula. It’s like assuming that it all sounded the same, rather than listening for what people in the past might have heard and searching for ways to make it audible again.

What is missing is not the text or the “performativity” but imaginative curiosity about the event itself where people participated in the prayer, where it unfolded. As the musicologist Christopher Small writes, “Most of the world's musicians—[meaning] anyone who sings or plays or composes—have no use for musical scores and do not treasure musical works but simply play and sing, drawing on remembered melodies and rhythms and on their own powers of invention… For performance does not exist in order to present musical works, but rather, musical works exist in order to give performers something to perform.”(Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening, 7-8) If, as Small argues, “Music is not a thing at all but an activity, something that people do,” (p. 2) this suggests that like music, religion cannot be contained in a written text (or score) or a single individual (an isolated listener or performer). Instead, like music, these prayers and blessings only enter the world when they are done by people and become events. But what does that tell me about my dried-up ancient texts—what kind of event is a prayer; what does it sound like?

III “Smoking a Lot of Pot and Reading the Bible” Consider a very loud, stupid thought experiment

Figure 3: Cover of Sleep, Jerusalem

A couple of years ago I started thinking about an ancient musical liturgy—but not a real one. That is, this ancient liturgy existed and you could listen to it any hour of the day or night, but it was fictionalized. This is the band Sleep’s infamous Jerusalem (1996). Formally it is a 53-minute raga in seven sections where voice, bass, and amplified guitar hover over then swoop back down to a dark, throaty, ringing chord in the key of C, while a drumbeat glides forward with a slightly delayed, quivering shudder.

To a listener unfamiliar with Metal’s subterranean Pentatonic growl, the whole thing could just sound like “distortion” at first, in the same way as a Hebrew liturgy might just sound like “a foreign language.” But tune in and you can hear something special happening. Both pop and classical music build their dramas by hinting at, but then delaying the key note of the song to build tension. This sound, called the tonic, is the particular pitch our ear is trained to expect and then wait for expectantly throughout the drama of the song, hungry for resolution (think of the sunny explosion in the chorus to “I Wanna Hold Your Hand”—that’s the tonic hitting). But “Jerusalem” instead builds by constant return to its pulsating tonic chord, like the constantly recurring “reciting tone” of a Gregorian chant. Rather than triggering an anxious search for the tonic, “Jerusalem” amplifies it, anchors the listener there and bathes them in it.

The tone might be described as a pipe organ at the center of the earth playing loudly enough that it can somehow be heard with perfect clarity in your room. The somber ambiance and the sheer conviction in the performance belie its playful, even bizarre content as it intones a scripture that never existed, one which narrates Genesis and the Crucifixion with the burning of cannabis in place of sacrifice. If there was ever a piece of music that mocked at the barriers between serious art and a baffling joke, this would be it.

Accounts of its creation are equally legendary: signed to a large record company during the post-Nirvana “grunge” feeding frenzy of the early 90s, the members were supposedly asked by an interviewer what they were doing to prepare for their major label debut. “Smoking a lot of pot and reading the Bible,” they answered. One of the most storied heavy metal albums recorded, Jerusalem is a unique musical achievement because it feels impossible yet completely believed-in.

Figure 4, Cover of Sleep, Dopesmoker

In this loud, stupid thought experiment, Jerusalem—now restored to its original title of Dopesmoker is a Dungeons and Dragons version of prayer that can help train our imaginations by blowing our minds, or at least our eardrums. Like D&D, it lets us roleplay liturgical experience in an exaggerated form. Its larger-than-life dimensions may help illuminate some minute, faded aspects of religious texts as events.

IV Can You Play a Myth? Jerusalem attuned me to the building blocks of an actual ancient prayer, Avinu Malkeinu

Listening to “Jerusalem” felt like participating in a fiction, but an ecstatic one. What haunted me was the thought that in listening to things like this I might be able to glimpse the building blocks of the ecstasy itself. Not so much an instantly effective, performative set of words or a religious experience as the elements that once constituted an event.

I began to wonder whether there was another way to look at the event of prayer when singing an ancient one to myself to a remembered tune, alone on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year. It was Avinu Malkeinu (“Our Father, Our King,”) a plea for mercy at the last possible moment of the holiday. I didn’t know where the melody came from, but it felt like I had always known it.

The command to perform this ritual dates back to the Iron Age: Leviticus 16, with its sacrifice to the otherwise unknown Azazel seems archaic and out of place even in ancient Priestly literature—it certainly seemed that way to Rabbinic commentators. Nachmanides’ commentary on it is less an explanation than a metaphysical outburst, where he as much as admits the presence of a second, alien god in the ritual. But the ways that Yom Kippur was lived out, the ways it was brought home, arose bit by bit, blossoming in late antiquity and the middle ages. The words, the melodies, the rituals, were built up in layers, but they are now all available at once, to enact the earliest impulse.

But I need to know why the song felt the way it did. Grand and old, yet almost desperate--like some dignified thing in urgent need. I wasn't sure how to find an answer, so I set out to learn to play it--first in a fumbling way on a guitar I'd picked up in front of an Oakland high-rise, then eventually under the tutelage of an expert in Turkish music named Jeff Matz who played deafeningly loud, mythic-sounding music with a band called High on Fire. Matz helped me understand its peculiar melody, based on the unusual scale it was in, called Phyrgian Dominant (or "Freygish" in Yiddish). Weirdly, while this scale is widespread across the world it is rare in the music of the Christian West, and often described as somehow specially “Jewish.” I wanted to know this dark, searching sound that was intertwined with my own childhood and life commitments. What part of the past it connected me with; what made it religious.

As the cantor and musicologist Gordon Dale wrote of the tune,"Many composers have set Avinu Malkeinu to music, but one particular melody is so popular that it is simply the default in many Ashkenazi synagogues . ... The origin of this melody is unknown [but o]ne cantor confided to me that while there are many other melodies for Avinu Malkeinu that he would love to select during High Holy Day services, his congregation would revolt if he denied them the opportunity to hear and sing this one.” (“The Music of Avinu Malkeinu,” in Lawrence Hoffman, ed. Naming God, 67)

Dale’s reflections suggested to me how a ritual event can change you--the circumstances in which simply enacting a pattern of sound does make you a different type of being:

...Those of us who were raised hearing it invest it with a great deal of personal meaning. ...As we plead to our father, our king, it is only fitting that we join together and lift our collective voices as brothers and sisters, all under the dominion of the God whom the song acknowledges. The opportunity to melt into a collective through song can be a powerful reminder of the connection shared by Jews and the unity toward which we strive.

Here he hit on something in the mystery of a musical text when it is not just on paper but enacted in a ritual event. The group pleading to someone who is ours necessarily implies an us, but not just any us--an us rooted in an intangible but specific way of being, not just of being religious or speaking a language but of singing.

Dale continues,

Another reason, I believe, that the ‘traditional’ melody is so well loved is that it simply sounds Jewish. Western music is largely built on an octave of clearly distinguishable notes along a certain scale of intervals. Much music of Jewish prayer works instead with modes, larger tonal patterns that change depending on the liturgical occasion. Avinu Malkeinu is composed in the musical mode known as Ahavah Rabbah or Freygish, the same mode that gives Hava Nagilah its Jewishness. In Avinu Malkeinu the characteristic sound of Ahava Rabbah can be heard in the descending melody of the word malkeinu (mal-KAY-AY-AY-NOO); sing it to yourself--you'll hear it. In musical terms we refer to this mode as having a flat two and an augmented second between the second and third scale degrees. Nonmusicians might just call it ‘Jewish.’ (p. 68)

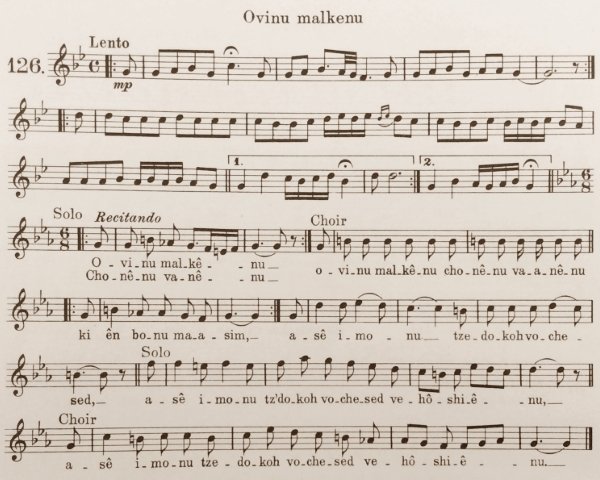

Pause for a moment and listen to the opening strains:

The first thing learning this musical mode did for me was to destroy the divide I'd imagined between "Western" and "Non-Western" music. To the extent those worlds are real at all, Ahava Rabbah is firmly planted in both, shared across parts of the world in an irregular web of connections, from Spanish Flamenco and Klezmer to South Asia. In the music of Turkey and the Arab world--but also the Eastern European synagogue--it extends beyond a simple inventory of notes to a whole mode, a productive set of rules and possibilities for playing (called a Maqām in Arabic).

Even as it is a key condition of collective Jewish being on Yom Kippur, the contours of this traditional Askenazic melody—its building blocks—extend unevenly across great swaths of time and space. It would be 100% at home in the Arabic Hijazi Maqām, the Turkish Hicaz makam, and their Andalusian ancestors, as well as the surf song "Miserlou" as covered by Los Angeles punks Agent Orange. But sung with the right intentions, it can make you not just Jewish but more urgently, decisively, needfully Jewish than at any other moment of the year.

The religious experience of Yom Kippur liturgy, in other words, was not just a thing in my head but a definable, external activity shared with many other people. The building blocks that philologists find to be missing cannot be located because they do not inhere in any one part of the ritual, not in the ritual rules for the event, the melody, the words, or the participants. There is no mysterium tremendum, no numinous thing, outside of the event. What happens is co-created by participants in a historically specific event, that draws on previous historical events, over the course of the time in which it unfolds.

V Music of the Ages in addition to scales, other musical elements are conveyed across borders of time, space and culture, tying one distinctive era or religion to another distinctive one

How far back can this music take us? There have been two schools in studying the history of Jewish music—the “eternal Jewish essence” school and the “no essence” school. The biggest argument for an essence was made by A.Z. Idelsohn in laying the foundations of Jewish musicology, documenting threads of ancient continuity and crucial differences in what had been mostly unwritten musical traditions in the ten volumes of his Thesaurus of oriental Hebrew melodies (1914–32). And as a byproduct he ended up documenting the Arabic and Turkish systems of melodic modes (maqāmāt or makamlar) that had been mostly invisible to European scholarship.

Later 20th century scholarship focused on the nuances of cultural borrowing, seeking to debunk the idea of deep continuity—Kay Kaufman Shelemay’s “Myths and Realities in the Study of Jewish Music” argues that Jewish music in every era has always been mainly absorbed from what is around it. Yet Shelemay’s “realities” can seem isolated in the present, since her study completely avoids discussion of liturgical sound performance before the modern period, including the melodies in the Bibical cantillation system or the early medieval Andalusian and Jewish nuba modes (an ancestor of Maqām). For the notes of the Hijaz Al Kabir mode preserved by Andalusian Jews are audibly identical to those of Ahava Rabbah. While it is absurd to claim you can step in the same river twice, because the water comes from somewhere else and is headed somewhere else, it is equally absurd to refuse to admit you’re wet, because that’s a river and you’re standing in it.

Musical rules and techniques are powerful cultural connectors because they are tricksters, shapeshifting to fly under our radar in remarkable ways. Indeed, it is the ability to fly under conscious perception, the almost-invisible way they can shift the feel or rhythm of an event-- that makes them so powerful. They can be at once very specific to a culture and historical moment, but also share specific patterns over hundreds of miles and years.

So while we must start from the uniqueness of each culture and musical event within it, we can also find threads that connect us to a deep past. Indeed the study of archaeomusicology documents specific musical techniques that connect us with the time of the original Sumerian tales of Gilgamesh. While the first serious written stories and the first accounts of musical tuning both date to around 2000 BCE, a 26th-century BCE Sumerian lexical list already enumerates among its types of instruments the kinnaru (a West Semitic name known from the 18th-century BCE Mari letters and 13th-century BCE Ugarit), and later Biblical Hebrew kinnor. The musical instruments developed in Mesopotamia and later adapted in Israel and Greece are among the oldest complex tools human beings have created: imagery on early seals already depicting lyres and fretted lutes suggest that the musical techniques predate the writing system itself.

Figure 5, Plaque with musician playing a lute, Ischali, Isin-Larsa period, 2000-1600 BC, baked clay - Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago

It was a detail I picked up from my music teacher that showed me a practical basis for these long-range continuities, one way they could work in practice. When Shulgi, the most famous early Mespotamian king, boasts of being not only a master warrior and writer but a master musician, he is intriguingly specific about what he can do. Shulgi brags about how he knows how to correctly place the frets on the neck of a lute, altering the distances between notes and thus the feel of the music. The most plausible translation reads:

I, Šulgi, king of Ur, have also devoted myself to the art of music. Nothing is too complicated for me; I know the full extent of the [strings] tigi and the [drum] adab, the perfection of the art of music. When I fix the frets on the lute, which enraptures my heart, I never damage its neck; I have devised rules for raising and lowering its intervals. (Shulgi Hymn B; cf. Hymn C)

Now, the way Shulgi changed the notes his instrument could play isn't something you can do with a modern guitar, but it’s been normal on the Turkish Saz for centuries—a version of which I’m learning to play. The frets that determine a normal guitar's intervals--how far apart its notes are--are rigid, made of metal and glued solidly into the neck. But ancient lutes--as well as many modern Turkish Baglamas--have frets that are just strings that are tied around the neck and slid to create the desired pitch and interval. In order to raise or lower them so they sound like music, you have to have a perfect ear and eye.

And it is this principle of fretting that seems to have facilitated the development of music theory itself, the very terms we use to describe what musics have in common. The possibility of fretting, of shortening the resonant part of a string allowing it to make more than one note, is probably what led to the study of sound ratios and theory about sound. As the archaeomusicologist Richard Dumbrill writes, “the lute not only dates but also locates the transition from musical protoliteracy to musical literacy: once proportions became tangible to the theoreticianís reasoning the notation of ratios such as those seen in the [various Babylonian tuning and music notation texts] and so theory was borne.” (Archaeomusicology 310).

VI We Can Remember it For You we have seen how attunement to the building blocks of the ritual event of a Yom Kippur prayer opens up concrete connections between ancient and modern Mesopotamia and America; attunement to this prayer also leads to a connection between Eastern Europe and America and a single teenage refugee’s experience

As with ancient Near Eastern music, harmony was not a value in traditional Jewish music because like Arabic, South Asian, and many other forms throughout the world, it focused instead on richly elaborating the expressive melody of a single voice--monophony. Yet precisely the same sounds that united Jewish worshipers in the familiar music of a prayer alarmed Christians whose ears and minds were trained to hear it as anti-musical.

Ruth HaCohen’s The Music Libel Against the Jews shows how European Christians viewed this monophonic Jewish liturgy as wildly excessive and disruptive, embodied in an antisemitic simile, ein Lärm wie in einer Judenschule, “a racket like in a synagogue.” And indeed formally, Jewish music and prayer absolutely did break the rules of “good” Christian harmony. In fact, it didn’t have any.

Jewish and Arabic sounds were considered chaotic because they focused on one voice or melody, not multiple voices strictly regimented into set intervals like chords—a tight order that early modern Christian thinkers saw as inherent to the cosmos, the “harmony of the spheres.” That Jewish melodic voice often moved differently from the evenly-spaced diatonic, major-minor scales on which much Christian classical music was based. The skipped steps and clustered tones of certain Jewish as well as Arabic modes instantly evoke a different realm to the diatonically-accustomed ear, from elsewhere or another time.

But with emancipation, Jews tidied up and harmonized, regimenting their spaces and prayers in tune with post-Enlightenment Protestant forms and sounds over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. Just as the first Reformers were installing good Lutheran-style polyphonic organs in synagogues, the 1810 Westphalian Synagogenordnung decree banned informal group prayer outside the synagogue and required silence when the Cantor was singing, only responding as a congregation in standardized ways. Official prayer had been pried away from informal “folk” settings and “disorderly,” improvised and unsynchronized congregant responses, which formed what musicologists describe as heterophony—multiple unregimented voices together.

Figure 6, Streisand and Avinu Malkeinu

This is why Jewish music felt to me like a victim of its own success, hemmed in on one side by the post-Lutheran conventions of synagogue performance and on the other by the potential of Ashkenazic cultural performance to read as Schmaltz. Barbara Streisand reciting Avinu Malkeinu is stunningly good—the melody was actually written by Rabbi Wolf’s own music director, the brilliant Max Janowski—but it still feels over-familiar to me, like Barbara Streisand reciting Avinu Malkeinu. The more intimately familiar it has become, the harder it can be to hear the starkness of its poetry and mesmerizing, “non-western” texture of its melodies.

One day, while investigating exactly how far back we could trace the non-Lutheran, Jewish Lärm-liturgies of the past, I found it. The first recording of the melody. What shocked me was the human impact it showed, of just how negatively European Christians had heard Jewish voices, and their violent efforts to silence that supposed dissonance. The archivist Tamar Zigman tells the story of its otherwise unknown protagonist and an inspired collector, Ben Stonehill, who recorded his musical memories along with those of over a thousand refugees in the 1940s.

‘Many Holocaust survivors served as experts for [Stonehill’s] project, their voices bearing the musical memory of what had been. On the recordings, various survivors appear one after the other as if on a conveyor belt. They are each asked to state their name, place of origin and age, and sing their song. In a recording from the summer of 1948, the voice of a young boy aged 16, a survivor of the horrors of the war who managed to reach New York, is featured. It was there, in the Marseilles Hotel in Manhattan, that Stonehill recorded him. “Eir naman? (Your name?),” the boy was asked, “Un vy alt bistu? (And how old are you?). The boy replied, “Zachtzen” (sixteen).” “Un vat vestu zingen?” (And what are you going to sing?) – “Avinu Malkeinu.”’

His name was Isaac. And what he sings, while identifiably our “Avinu Malkeinu,” took what was for me a staggering twist: He begins half-mumbling near the climax, then picks up the plea to God, “our father our king”—traditionally the pinnacle of the song is:

Asei imanu tzedaqah vechesed vehoshieinu

“Be just and be kind to us, and rescue us.”

Instead Isaac, who was saved from God knows what to get to New York and stand in front of Stonehill’s microphone, sings twice, his voice picking up steam:

Asei imanu tzedaqah vechesed vehoshieini

“Be just and be kind to us, and rescue me.”

Figure 7, First Written Transcription of Avinu Malkeinu

Someone did. Isaac’s testimony has not been well cared for, despite the fact that it is the earliest and most direct link to the world the melody came from, a world Europe destroyed. A meager few blog posts at least celebrate the work of curating Stonehill’s archive, but they are not much help in searching it, citing and linking less than 1/5 of its contents according to no method I could find. Isaac’s recording is not among the links.

Up until last year, Zigman’s essay linked to it, then was relocated, sans link. As far as I know this is now the only place you can find it.

The world is now full of crisp, well-recorded versions of Avinu Malkeinu, but this first one bears the mark of a Jewish experience quite different from the others. In Isaac’s performance and the grammar of his prayer you hear the terror, mercy, and rescue he had encountered.

VII Dead Listeners, Living Incantations A second Yom Kippur prayer gives us a chance to further explore this approach by replicating the building blocks of an event which seems to have transformed the thinking of Yom Kippur’s greatest philosopher, elements we can share with this dead listener.

The most famous religious experience of music in Jewish philosophy is Franz Rosenzweig’s decision to reject his planned conversion to Christianity and remain a Jew after hearing Kol Nidre, the opening prayer of Yom Kippur. The legend goes that Rosenzweig, persuaded to convert after long conversations with a fellow assimilated Jew, decided he would attend Yom Kippur services one last time.

There he heard Kol Nidre at a small synagogue in 1913. As the Times of Israel writes, “Jewish history is replete with influential, secularized thinkers who were ‘converted’ back to Judaism by this prayer [with] theologian/philosopher Franz Rosenzweig, perhaps the most famous of all to have a significant spiritual awakening following the Yom Kippur prayer.”

As Hadassah magazine tells it, “The haunting melody touched the heart of Franz Rosenzweig, who upon hearing it, decided not to convert to Christianity.” Indeed, it is an important enough part of the Jewish narrative around Yom Kippur that it appears in the Sefaria study sheet:

The great Jewish philosopher Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929), was getting ready to leave the faith altogether in 1913. Before he took that fateful step, he attended services at a small synagogue in Berlin. After hearing Kol Nidre, and the rest of the Yom Kippur prayers, he had a mystical experience that renewed his identity and set him on a course to renew and strengthen and deepen his faith and the faith of others through his writing and teaching. https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/344251?lang=bi

Figure 8, Franz Rosenzweig with his Dad and his Mom, the Only People Who Know what he Heard

But Rosenzweig himself says no such thing, and there is not a shred of direct evidence of this “mystical experience.” Instead, his first biographer Nahum Glatzer writes that he knows this because he heard it from Rosenzweig’s mom. After reasoning that Rosenzweig was converted not by Kol Nidre but by hearing the Shema and the shofar, he writes:

Rosenzweig left the services a changed person…[but] He never mentioned this event to his friends and never presented it in his writings. He guarded it as the secret ground of his new life. The very communicative Rosenzweig, who was eager to discuss all issues and to share all his problems with people, did not wish to expose the most subtle moment of his intellectual life to analysis and “interpretations.” His alert mother realized immediately the connection between her son’s attendance at the Day of Atonement service and his new attitude and later confided this conclusion of hers to the present writer. (Glatzer, Franz Rosenzweig: His Life and Thought, p. xvii) [KD3]

Glatzer goes on to make a strong argument that things must have changed for Rosenzweig on Yom Kippur because less than two weeks later, he first announced that he has reversed his decision to become Christian, and his writing makes clear the decisive importance of the holiday as “a testimony to the reality of God which cannot be controverted.” (Almanach des Schocken Verlags suf das Jahr 5099, 1938, p. 60, cited in Glatzer p, xx) In his major work, the Star of Redemption, he testifies starkly to the importance of this ritual as a “transition from creation to revelation” in which “Man is utterly alone on the day of his death…and in the prayers of these days he is also alone.” “They too set him, lonely and naked, straight before the throne of God.” [1]

What kind of experience does the melody itself afford? Perhaps the deepest and boldest exploration was by the early Freudian analyst Theodore Reik, who dedicated a chapter of his 1919 “Ritual Psycho-Analytic Studies” to it:

The deeply affecting melody, to which has been set this apparently prosaic formula, is justified, since it is not related to the present wording, but to the secret feelings which have become unconscious. This music brings adequately to expression the revolutionary wish of the congregation and their subsequent anxiety; the soft broken rhythms reflect their deep remorse and contrition. Thus, the song is really full of terror and mercy, as Lenau has observed. The high mental tension, the contrition and bewailing of the congregation during this prosaic ceremony, do not refer to the actual formula they are repeating, but to its latent content.

Reik’s claim that the song is “really full of terror and mercy” sounds sweeping, like it refers to ineffable things that could not possibly be contained in a piece of music. But in fact it has strong musicological justification.

Musically, it is a “sighing” melody, where the first phrase begins with a small downward step (a semitone from A to G#, the notably tense interval of a major Seventh, hovering just below the dominant starting note or “tonic”) then in the second phrase a downward plunge (three semitones down from G# to E) lingering on the low E in a quavering, blurry glissando before climbing back up to its starting note, the tonic note of A. From there the melody begins to strain upward (a whole tone from A to C) on the fifth phrase before soaring seven semitones up to hit its climactic high note of E on the sixth, penultimate phrase before descending.

Crucially, Reik is absolutely right that the musical drama, which quavers with half-steps in the depths below the key of the song in the first three phrases and soars upward on the fourth and fifth phrase, really does go far beyond the wording—there is nothing “climactic” about the wording of the fifth phrase, “vows which are abbreviated.” Indeed, in the standard English translation, the rhymes, the verbal music, the sense of an incantation, is not apparent:

כָּל נִדְרֵי All vows,

וֶאֱסָרֵי and things we have made forbidden on ourselves,

וּשְׁבוּעֵי and oaths,

וַחֲרָמֵי and things we have consecrated (to the Temple),

וְקוֹנָמֵי and vows issued with the expression “konum,”

וְכִנּוּיֵי and vows which are abbreviated,

וְקִנוּסֵי and vows issued with the expression “kanos,”

that we have vowed, and sworn, and dedicated, and made forbidden upon ourselves;

from this Yom Kippur until next Yom Kippur—

may it come to us at a good time—

We regret having made them; may they all be permitted,

forgiven, eradicted and nullified,

and may they not be valid or exist any longer.

Our vows shall no longer be vows,

and our prohibitions shall no longer be prohibited, and our oaths are no longer oaths.

We have one—powerful if not conclusive—proof of how Kol Nidre affected Rosenzweig—his need to personally translate it. That this specific prayer was of special importance to him within the Yom Kippur liturgy is shown by the fact that he translated it in a letter to Martin Buber of 1922. Rosenzweig’s stunningly rhythmic, incantation-like German version is remarkable because, unlike any English prayerbook rendering I have seen, it conveys both the timing and the grammatically-based rhyme of the Aramaic original.

Reading his version lets us attune ourselves to how it must have sounded to his ear. Indeed, this aspect of Rosenzweig’s religious experience is one we can most plausibly reenact and live again in our own way through the act of translating it publicly, as he did privately. To give a sense of how Rosenzweig’s German feels, what he may have heard, one could try again, to translate the prayer differently into English. I studied it with the musician and writer David Tibet, who has had some experience animating dead texts with his Thunder Perfect Mind album (yes, the Nag Hammadi tractate), a project for which he learned and edited texts in Coptic. This was what we came up with:

All vows we have bidden, all things we have forbidden, oaths given, hinted, hidden, made taboo or promised to, that we vowed or avowed, or gave to do or tabooed—from this Yom Kippur until the one to come …We renounce them all. May they all be permitted, forgiven, erased and made null, may they be made invalid and not exist! Our vows are no longer vows, what we forbad was not forbidden, our oaths are hereby ungiven.

I still don’t think you can freeze-dry experience or reconstitute what the refugee Isaac or the philosopher Rosenzweig felt. But the words, the tonality and scale, the performance style can be known. We can play the melodies they did, and if we are attentive enough, imagine what these past listeners heard. This last example suggests one method of moving from hidden, inner and private to explicit and public: by translating, by living through the words and music again.

And in the end, I still do not think we can get inside the heads of our subjects, between the dead listeners’ ears. But what matters is that we can get the dead words and sounds inside our own heads and ears, to understand them by participating in them. The whole enterprise can give us a bit of the moral courage Peter Brown described. In imagining, feeling, and translating these lost prayers we can find the building blocks of the events that past others participated in, to the extent that they can be shared with new others who hear it. This is one way we can find the courage to play with these old blocks and build something new that can turn our heads and let us hear, explore, and be haunted by what animated these past words.

[1] https://sandykress.wordpress.com/2019/09/26/thoughts-to-ponder-on-the-days-of-awe/. For the translation see Rozenzweig, Gesammelte Schriften 1: Letters, vol 2:832-33, #816.